|

|

|

‘Things. Places. Years.’ by

Anthony Auerbach (with German translation by Bettina

Steinbrügge)

in: Klub Zwei, in Zusammenarbeit mit,

edited by Annette Südbeck (Vienna: Secession,

2005), pp. 34–39; first

published in in Lasso, No. 1 (Lüneburg:

Halle für Kunst/Frankfurt am Main: Revolver,

2004) pp. 88–92 (German), pp. 151–153

(English).

Things. Places. Years. is a film about women I know by women

I have gotten to know; a film about women I have grown up with in London — women

to whom I owe my education — by women who have grown up and

were educated in Germany and Austria. It is a film about the knowledge

of Jewish women. That is, getting to know Jewish women and getting

to know what Jewish women know. The film records a process of coming

to terms with the knowledge of an absence: the absence through which

the past makes itself present in a city such as Vienna. Things. Places. Years. is a film about women I know by women

I have gotten to know; a film about women I have grown up with in London — women

to whom I owe my education — by women who have grown up and

were educated in Germany and Austria. It is a film about the knowledge

of Jewish women. That is, getting to know Jewish women and getting

to know what Jewish women know. The film records a process of coming

to terms with the knowledge of an absence: the absence through which

the past makes itself present in a city such as Vienna.

I first met Klub Zwei (Simone Bader and Jo Schmeiser) when they

came to London in 2000 to begin researching a project then without

a name. They did not introduce themselves as documentary film-makers.

They introduced me to a collaborative art practice focused on the

interrogation of women’s experience and an approach to media

in which forms of representation — graphics, video, text — are

understood as interventions in public space, that is, as interventions

in a public discourse rather than in a supposedly autonomous art

discourse. Klub Zwei’s (then) most recent project Work

on/in Public (Arbeit an der Öffentlichkeit, 1999),

developed in co-operation with MAIZ (an autonomous centre run by

and for migrant women) in Linz, Austria, resulted in a series of

posters based on interviews with women from various parts of the

world who had recently settled in Austria. The women’s remarks

on the present-day legal, social and political condition of immigrants

in Austria came to be seen in a sharper light, especially outside

Austria, after the success of Jörg Haider’s far-right

Freedom Party in the 2000 general election. One of the poster headlines

reads, in the words of one the women, ‘Austria never got over

the Hitler era.’

The initial motivation of Klub Zwei’s research in London

was to follow up their previous work by investigating the heritage

of emigration from Austria, that is, the presence in London of women,

their daughters and granddaughters, who had escaped — some only

narrowly — from the genocidal persecution of Jews during the

Nazi period. Jo and Simone were particularly interested to meet

women whose work involved them in the cultural sphere: in the production,

transmission and preservation of knowledge. It soon became clear

that this could be no objective documentation. It would be a conversation

which examined not only the émigré condition, and

the experience of the Holocaust, but also Klub Zwei’s own

position, in their words, ‘as descendants of the perpetrator

society.’ The project would establish its structure on the

axis Vienna-London, not by focusing exclusively on Jewish women

born in Austria, but by talking about women’s experience of

the city. The twelve women with whom Klub Zwei recorded interviews

come from diverse geographical and religious backgrounds and would

never conceive of themselves as a group. Things. Places. Years. asks

us to reflect on what these women might share, alongside the fact

that by chance or by design they have made their homes in London.

That is, to reflect on the construction of identity: what it means

when we identify ourselves or are identified by others as women,

as Jews, as migrants, as bearers or curators of a culture or a historical

experience.

In the interviews, history is refracted through the women’s

family stories: through their relationships with people, places,

things. However, it becomes clear that for many of the women, these

stories were not discussed in the family. Ruth Sands describes how,

if ever her father mentioned their life before emigration, whenever

he began ‘Bei uns in Wien ...’ (‘At home in Vienna

...’), her mother would interrupt angrily, ‘Es gibt

nichts zu sagen.’ (‘There is nothing to say about it.’)

She says of her mother: ‘She left Vienna and she was, I think,

thirty-three and it was as if her life started when she was thirty-three.’

Ruth Sands also tells how she attempted to protect her own children

by not discussing the family history. The acknowledgement of this

reluctance is echoed in different ways by several of the women.

Yet for all the women, there is no question that the history which

has marked their families in various ways is something that should

be known. One may also say that all the women recognise the desire

and the right of the next generation to know. In Klub Zwei’s

conversation with Elly Miller and her daughter Tamar Wang, Tamar

questions her mother and remarks how it was almost as if she had

never heard it before; how her sense of history was never a family

story, or at least that the family story was only ever pieced together

from things mentioned occasionally in the home and intermingled

with fragments of the bigger picture of history that was taught

outside the home. Elly Miller makes the point that her own childhood

recollections are also coloured by the knowledge, acquired only

later, of the monumental horrors which now seem to stand at the

centre of Europe’s twentieth century. Hearing my mother Geraldine

Auerbach speak to Klub Zwei and reflect, for example, on her father’s

family’s journey from Lithuania to South Africa at the turn

of the twentieth century, her upbringing there under the regime

of ‘separateness’ (apartheid) and her joy in the diversity

(the mixed-up-ness) of a city such as London, was to hear things

I know, but only vaguely — family things — expressed in

an unfamiliar way. My mother prefers, perhaps, to express what this

heritage means to her through her work as founder and director of

the Jewish Music Institute. This also suggests something about another

of Klub Zwei’s questions: about the women’s sense of

Jewish identity.

The crossing of history, identity and

work also emerges in what we learn of

Ruth Sands’s co-operation in the

Second Generation Trust, an organisation

founded by Katherine Klinger. The organisation

was started as a way of ‘bringing

out into the open the generational

consequences of history,’ specifically

for the post-Holocaust generation,

the generation for which the Holocaust

is nonetheless, as Katherine Klinger

put it to Klub Zwei, ‘part of

an unseen and unexpressed trauma.’ However,

the Second Generation Trust does not

focus only on how it has affected the

descendants of the survivors [note 1],

but includes the children of perpetrators,

collaborators and so-called bystanders.

Is the history from which Ruth Sands

derives her sense of Jewish identity

the same as that which makes Jewish

identity, for Katherine Klinger, hard

to grasp? Is the historical

‘rupture’ which is the topic

of the Second Generation Trust’s

activities echoed in the cultural displacement

felt by immigrants and their children?

Do we value these displacements as historical

reminders, that is, the vectors of a

history on which an identity might be

founded, even if a broken one? Is Jewish

history (and hence identity) unique

in being founded, it seems, on displacement

and remembrance?

Things. Places. Years. does not attempt to extract a consensus

from the women’s statements, nor impose one on it, nor is

it a history lesson. It is a film, that is, an intervention by Klub

Zwei. The film accepts the severity of cutting many hours of interviews

to seventy minutes. It suggests the telling of history as a form

of interrupted speech, remembrance as interruption in the present.

The cut permits the viewer to listen as if the women would speak

for one another, and so, their differences in experience, in expression,

in opinion, emerge as an equivocality in the identity we have projected

on them. The cut works because of Klub Zwei’s consistent attentiveness:

on a single page such as the poster Bei uns in Wien, on

many pages such as the book Things. Places. Years. The Knowledge

of Jewish Women (which forms an extensive record of Klub Zwei’s

conversations and from which I have quoted), in five minutes of

voice and text such as Schwarz auf Weiss or in seventy

minutes of interruption documenting the presence of absence.

Anthony Auerbach

Los Angeles, January 2004

... return ‘Hallo Wien’ ... return ‘Hallo Wien’

... return: Urban matters ... return: Urban matters

Note

-

This is the focus of the Second Generation

Trust. Many of the survivors lost their

parents, thus they are the children

of the

‘victims’ (A common childhood

experience of the second generation

was that it was always other people

who had grandparents). But the identification ‘victim’ can

be problematic. The phrase ‘victims

of the Holocaust’ perhaps

falsely dignifies their fate. To acknowledge

that the grandparents were murdered

by the Nazis could be more to the point. [back to text]

References

Things. Places. Years.

(2004, DV-CAM, colour, 4:3, stereo,

70 min, English with German subtitles)

a film by Klub Zwei (Simone Bader & Jo Schmeiser)

Things. Places. Years. The Knowledge of Jewish Women

(2004, 300pp, 140 x 202 mm, English and German)

a book by Klub Zwei (Simone Bader & Jo Schmeiser)

Bei uns in Wien/At home in Vienna

(2002, 594 x 841 mm)

posters by Klub Zwei (Simone Bader & Jo Schmeiser)

Österreichischer Grafikpreis, Innsbruck, 2002

with: Geraldine Auerbach, Josephine Bruegel, Erica Davies, Lisbeth

Perks, Katherine Klinger, Elly Miller, Rosemarie Nief, Anni Reich,

Ruth Rosenfelder, Ruth Sands, Nitza Spiro, Tamar Wang

Schwarz auf Weiss — Die Rückseite der Bilder

(2003, Mini-DV, B&W, 4:3, stereo, 5 min, Polish, French, Bulgarian,

English and German)

a video by Klub Zwei (Simone Bader & Jo Schmeiser) with Rosemarie Nief

Images

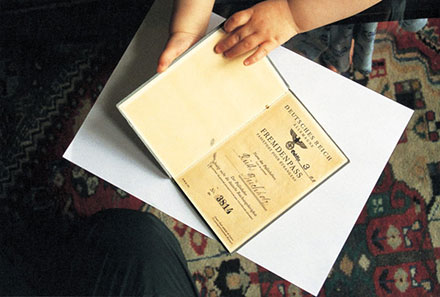

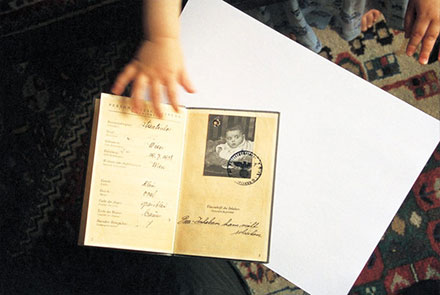

Passport of Jewish girl born in Vienna in 1938, held by her granddaughter in 2001, photographed by Klub Zwei

|

|

|

|

|

|