|

|

|

‘Hallo Wien: The Appearance

of Klub Zwei’ by Anthony Auerbach, 2006.

This article was prompted by the reappearance in

Vienna of

an article I had written in 2004

on Klub Zwei. I wrote ‘Hallo Wien’ for an

art magazine published in Vienna but it

was rejected by the editors, though they had previously

welcomed my proposal.

‘Things.

Places. Years.’ by

Anthony Auerbach (with German translation by Bettina

Steinbrügge)

in: Klub Zwei, in Zusammenarbeit mit,

edited by Annette Südbeck (Vienna: Secession,

2005), pp. 34–39; first

published in in Lasso, No. 1 (Lüneburg:

Halle für Kunst/Frankfurt am Main: Revolver,

2004) pp. 88–92 (German), pp. 151–153

(English).

The point is to describe appearances. The point is to describe appearances.

In 2005, works by Klub Zwei (Simone

Bader and Jo Schmeiser) appeared in Vienna: posters along tramline

D as part of the Art in Public Space project Works Against Racisms

[note 1], new video works at Secession in their

own exhibition entitled In Co-operation With [note

2], recycled works in How Society and Politics Get in the

Picture [note 3], a group show at Generali

Foundation. The book Things. Places. Years. The Knowledge of

Jewish Women [note 4] appeared in print and

the film Things. Places. Years. [note 5]

was screened several times along with various public discussions.

Mostly I was not there. But, since an

article I wrote about Things. Places. Years. was reprinted

in the Secession catalogue, I also appeared in Vienna — from

a distance. My location at the time of writing (Los Angeles, 2004),

which had appeared at the foot of the piece when it was first published,

unexpectedly rose to the top when it was reprinted in Vienna. I

had written about getting to know Jo and Simone in London and about

how they got to know the women who took part in Things. Places.

Years. I described the film as recording 'a process of coming

to terms with the knowledge of an absence: the absence through which

the past makes itself present in a city such as Vienna.' [note

6]

Reading my article again in 2005, meant coming to terms with my

own presence in Vienna and confronting how Klub Zwei's work appeared

in the city. Writing again means attempting a site-specific interpretation

of Klub Zwei's appearances. The critique is therefore addressed

to Vienna.

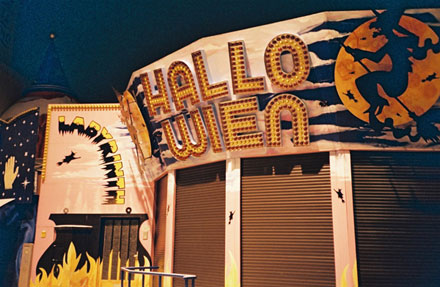

Hallo Wien. This is where I want to start. At

an exact address: the Second District, at Rondeau, near the corner

of Leichtweg (Easy Way), between an astrological kiosk and Hell.

At the heart of the Prater, Vienna's permanent funfair, 'Hallo Wien'

appears above the door of a labyrinth: a maze of mirrors, invisible

barriers and deceptive surfaces, entrance two euros. There is not

much difference between here and the city on the other side of the

Danube Canal. The zone of sensation, chance and mechanical entertainment

repeats its past and declares its modernity as vehemently as the

city whose officials assert it to be the 'world capital of culture'

[note 7]. The difference is only that the Prater

is somehow exempt from the city's regime of repression (which it

does not contest).

I choose this location because it is inside the city limits. The

place does not give me a distance, still less objectivity, but instead,

the possibility of making things visible. The other places I shall

discuss are where Klub Zwei's works appeared.

It is no surprise that the monsters which advertise the trivial

terrors of the Prater's ghost trains — reinstated after the

Second World War — preserve the grotesque anti-Semitic and

racist caricatures which haunted European culture for centuries.

It is no surprise either that the city of culture should shun such

obviously vulgar configurations of fear.

Bei uns in Wien (At home in

Vienna) is a work by Klub Zwei produced on posters and in the press

(2002). The words come from interviews with women in London, mostly

Jewish women, some of them born or brought up in Vienna until forced

to leave because of anti-Semitic persecution. Klub Zwei's work,

that is, selecting the words and embodying them in a distinctive

graphic identity — a stark, black-white-red typography they

have developed using a typeface originally designed for airport

signage — brings the message home [note 8].

In a passage cut out by Klub Zwei, Ruth Sands remembers her parents

speaking about Vienna. Whenever her father began, 'Bei uns in Wien

...' ('At home in Vienna ...'), her mother would interrupt angrily,

'Es gibt nichts zu sagen.' ('There is nothing to say about it.')

'She left Vienna and she was, I think, thirty-three and it was as

if her life started when she was thirty-three.' [note

9]

Klub Zwei want to speak about the legacy of emigration, for the

survivors of the Holocaust and their children, and for the place

from which they fled. Klub Zwei's work hints, without saying anything,

at the distortions in language and society inherited and propagated

by the descendants of those who permitted, supported, facilitated,

executed or benefited from the persecution, expulsion and murder

of the Jews of Vienna.

Secession, Association of Visual Artists, 1., Friedrichstrasse

12, entrance six euros (includes the Beethoven Frieze)

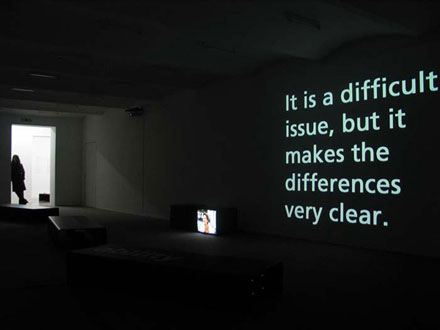

Appearing again in a video by Klub Zwei recorded

in Vienna in 2005 and exhibited in the basement of the Secession,

Ruth Sands has not much to add to her mother's silence about Vienna.

She can speak a little of her feelings as a visitor. She can speculate

with Katherine Klinger (who also takes part in the video) on a personal

history without the interruption of emigration. But this speculation

leads nowhere. The two of them wonder who in Vienna knows or cares

that the city lost some 190,000 inhabitants. [note

10]

What Ruth's mother cannot speak about, Vienna passes over in silence.

But whereas Ruth's mother's silence insisted on interruption —

an irreparable break in her life — it is as if Vienna's silence

claims the opposite. It is as if for Vienna, losing its Jewish population

— many of whom were influential in the artistic and intellectual

life of the city — is not a cultural catastrophe from which

the city has never recovered (as seems obvious to Ruth and Katherine),

but rather a misfortune which luckily did not happen to 'us' the

Viennese, but happened to 'them' the Jews.

Klub Zwei's aim, 'in co-operation

with' [note 11] the women who speak in the videos,

to expose Vienna's silence, is to interrupt it: to break the self-serving

illusion of continuity which allows Vienna's official culture to

celebrate the achievements of artists and intellectuals in the city

in the first decades of the twentieth century without acknowledging

how the conditions of such production were destroyed. Klub Zwei's

didactic insistence — how they address their audience —

however, inscribes a division between the 'perpetrators' and the

'victims' which undermines the co-operation with a twofold effect.

On one hand, reinstating the notion of 'us' and 'them' tends to

exonerate the non-victim, the fortunate one, even when it does not

explicitly blame the victim. On the other hand, in accordance with

the norms of art (as upheld by institutions like Secession), the

split encourages the viewer to identify with the victim, and hence

narcissistically to recoup the pathos the viewer projects on the

image of the victim. Moreover, there is no ambiguity in the interview

structure about who is asking the questions and who is supposed

to answer them.

This is why the Secession president, in his catalogue

foreword, is so sure there are no doubts 'about the side Klub Zwei

is on' [note 12], although he does not say which

side this is. Klub Zwei themselves say they to belong to the majority,

'perpetrator' side. Theirs alone among the commentaries published

by Secession asserts this position. By contrast, other essays in

the same catalogue, while recognising the necessity and difficulty

of Klub Zwei's work, produce a fog of tortuous or misleading locutions

aimed at disclaiming responsibility.

For Hannah Fröhlich, who appears in another video presented

by Klub Zwei in the same basement installation, the lure of identifying

with the victim is why working together does not work. She explains

to Klub Zwei that, in her view, only intensive personal and individual

reflection would bring about any changes. But she is not hopeful

that Austrians are willing to go beyond comforting generalisations

or sentimental dependency on 'victim'-ciphers and instead examine

the history of their own families and institutions. For her part,

Hannah's own experience and reflections on growing up, living and

working in Vienna as a Jew have led her to hand over the responsibility

she once imposed on herself as a writer and journalist for (in her

words) 'pointing out all the atrocities here'. 'Now,' she says,

'I only do it when I feel like it. When I have fun doing it.' To

me, this signifies that a Jewish woman minding her own business

is capable of causing panic in Vienna, and she is aware of this

power.

Tramline D, 3., 1., 9., between Südbahnhof and Althanstraße,

€1.50 a ride, free if you walk

In July 2005, tram passengers might have noticed a series of posters

at along the route with slogans like, 'Austria needs an anti-discrimination

law.' and 'We are black. We are qualified professionals. We demand

access to the labour market.' The work of Klub Zwei in co-operation

with the Black Women's Community (a small non-governmental organisation,

run by and for black women, focusing on developing workplace opportunities

for black women and anti-discrimination outreach) would seem to

offer the chance to step outside the limits of art practice and

the social constraints of institutions like Secession. However,

the posters appeared on the streets not as part of a political or

an advertising campaign, but as the result of an Art in Public Space

commission. Statements such as the ones I mentioned already, or

'Get rid of the Ausländerbeschäftigungsgesetz [law restricting

the rights of foreign workers in Austria] now!' are controversial

in Austria and one should question why they are not part of everyday

political discussion, why a vigorous campaign to implement the necessary

legislative changes (if only to conform with EU standards) is not

carried out by any political party and why raising awareness of

workplace discrimination is not carried out by any government agency.

However, in the present context, questioning the meaning of Art

in Public Space is more to the point.

Art in Public Space is an initiative

intended, according to an official statement, 'to further consolidate

[the City of Vienna's] position in the visual arts.' [note

13] A brief look at an example is probably the best way to read

between the lines. Handlungsanweisen (Instructions) is

a project originally launched by Kunsthalle Wien as a permanent

installation and adopted by Art in Public Space as a temporary one:

as a step towards the City's goal of 'enhancing' the Karlsplatz

area 'as a leisure-time attraction.' 100 artists accepted the commission

to devise instructions addressed to passers-by which were posted

around Karlsplatz and Resselpark on bright yellow notices advertising

the Kunsthalle. They thus assume a place in a system of authority:

the art institutions (and ultimately governmental authorities [note

14]) decide who qualifies as an artist and therefore who is

authorised to instruct the public. The instructions of course have

no effect, except to inscribe this hierarchy in 'public space' and

instrumentalise the artists' statements alongside other measures

(such as by-laws, defensive street furniture, increased lighting,

video surveillance and police patrols) the City is deploying towards

achieving its goals for this 'problematic urban zone' [note

15]. The chief function of the artists' work is simply occupation:

taking up the space in public which might otherwise be appropriated

for some unauthorised message or intervention.

Most public art projects are more subtle and probably more effective

in extending the control of so-called public space and defending

it for the leisure class. In a place like Vienna, whose city centre

is already dominated by cultural institutions and their exclusive

publics, Art in Public Space recruits artists to the cause of preventing

the contestation of public space.

Unusual occurrences such as the appearance of slogans calling

for an end to racial discrimination in the job-market are harmless

as long as the worst they threaten is an art scandal and a tedious

discussion about what is or is not art. Appearances such as Klub

Zwei's contribution to Works Against Racisms serve the

sponsoring authorities because, in so far as they are mediated by

recognised and approved artists, using an elegant and accepted visual

language, they create the false impression that the issues they

evoke are a significant part of public discourse. The result is,

public scrutiny is deflected from the reality that such issues are

officially neglected, and the possibility of a political intervention

in public space — by black women, for example — is undermined.

The Black Women's Community welcomes the co-operation with Klub

Zwei and the association with Art in Public Space, because they

know well enough that an alliance does not require identical interests.

They know that the artists will gather the approval of their peers

while they, the black women, will run the risk of public hostility.

Nonetheless, it is important for them to appear in public, for their

statements to be visible, and where possible to gain sympathisers.

In any case, they were not planning any major demonstrations. As

Beatrice Acheleke, founder and chairwoman of the Black Women's Community

explained to me, as long as minorities are as vulnerable as they

are in Austria, mobilising communities to collective action is extremely

difficult. 'Paralysed' is the word she used. It must be made clear,

however, that social paralysis affects the whole body politic.

Generali Foundation, 4., Wiedner Hauptstrasse 15, entrance

six euros

Following an invitation to take part in a group show on a political

theme, Klub Zwei suggested exhibiting their recent co-operation

with the Black Women's Community. The organisers also agreed to

place a banner reading 'Respect and rights for visible minorities!'

on the street where they usually advertise the current exhibition.

Inside, the tramstop poster designs were reproduced, reduced in

size, on specially-made panels. Visitors were also provided with

background materials to browse. The rest of the exhibition included

works by eight other artists from the 1970s to the present day,

some from the Generali collection (e.g. Adrian Piper's Black

Box/White Box, 1992), others on loan (e.g. Hans Haacke's Gallery

Goers' Residence Profile, Part 2, 1970–71).

Here, in a private art museum, the meaning of

the slogans, which had survived the negotiations, compromises and

crossed purposes it took to get the posters out on the street, is

engulfed by the meaning of their appearance. That is to say, in

this environment, the specific content of the work and the original

motives for making it tend to be reduced to 'society and politics'

in general. 'How society and politics get in the picture' is a question

of comparative aesthetics in which the artists are privileged, but

still cannot determine the meaning of their work. The banner which

stood in for the exhibition advertisement, with its apparently unambiguous

slogan, displayed the irony of using the term 'visible minorities'

to mark the place where the people to whom it refers are made invisible

[note 16].

A museum functions to authenticate the objects it assembles, while

isolating them from the actual social and political contexts where

they first emerged and where they re-emerge from the archives. Under

the regime of art, does it matter which war Martha Rosler feels

bad about? Does it make any difference if you are confronted with

injustice and brutality from Los Angeles in the 1990s or present-day

Vienna? Are visitors to the Generali 'foundation' any more or less

mystified by the addresses of New York gallery goers in the 1970s

or the transcription of antique fantasies of a world government?

Once society and politics 'get in the picture', the viewer is only

required to make aesthetic judgements.

The more is required of the viewer, the more difficult the work

of Klub Zwei becomes (for the viewer and for Klub Zwei).

Anthony Auerbach

Vienna, February 2006

...

‘Things. Places. Years.’ (2004) ...

‘Things. Places. Years.’ (2004)

...

return: Urban matters ...

return: Urban matters

Notes

- Arbeiten gegen Rassismen, 1–31

July 2005, along tramline D between Südbahnhof and Althanstraße.

Project organised by Daniela Koweindl, Martin Krenn with Ljubomir

Bratic, Petja Dimitrova, Richard Ferkl, Anna Kowalska, Klub Zwei,

Daniela Koweindl, Martin Krenn, Schwarze Frauen Community. [back

to text]

- Klub Zwei. In Zusammenarbeit mit,

15 September–13 November 2005, Secession, curated by Rike

Frank and Annette Südbeck. [back to text]

- Wie Gesellschaft und Politik ins Bild kommen,

16 September–18 December 2005, Generali Foundation, curated

by Sabine Breitwieser. [back to text]

- Things. Places. Years. Das Wissen Jüdischer

Frauen, Simone Bader, Jo Schmeiser (eds.), Innsbruck: Studien

Verlag Tirol, 2005. [back to text]

- Things. Places. Years., 70 min, English

with German subtitles, 2004. [back to text]

- 'Things. Places. Years. a film by Klub Zwei'

in Lasso, Lüneburg: Halle für Kunst, 2004,

reprinted in Klub Zwei. In Zusammenarbeit mit., Vienna:

Secession, 2005. Read it here. [back

to text]

- 'Welthauptstadt für kultur': Festwochen

speech by Andreas Mailath-Pokorny. [back to text]

- Klub Zwei published the texts in 'alternative'

magazines such as Female Sequences and in the mainstream

press (Der Standard) under the auspices of Museum in

Progress, 2002. [back to text]

- Bei uns in Wien, poster, 2001. See

also Things. Places. Years. [back to text]

view poster (English) PDF

view poster (German) PDF

- Estimate including all whom the Nazis regarded

as Jewish, about 11% of the population. [back to

text]

- I understand the title of the Secession show

as a signal of Jo and Simone's collaborative practice and acknowledgement

of the other women's contributions to the work as interlocutors,

on or off screen. [back to text]

- Matthias Hermann in Klub Zwei. In Zusammenarbeit

mit., Vienna: Secession, 2005, p. 3. [back

to text]

- 'Ihre Positionierung im Bereich der bildenden

Kunst.' Art in Public Space is a joint initiative by City Councillors

Andreas Mailath-Pokorny (Cultural Affairs and Science), Werner

Faymann (Housing, Housing Construction and Urban Renewal) and

Rudolf Schicker (Urban Development, Transport and Traffic). http://www.publicartvienna.at

[back to text]

- Public funding of culture is not independent

of government in Austria, but is part of a system of patronage.

The artists and experts who sit on advisory panels are usually

also clients of the funding organisations and their decisions

are usually subject to political approval. [back

to text]

- Gerald Matt, curator's statement, Handlungsanweisen,

Kunsthalle Wien leaflet, no date. [back to text]

- One should also question the applicability

of the term 'visible minorities' in the Austrian context. The

term is used officially in Canada and occasionally in the UK to

refer inclusively to a variety of ethnic groups in the context

of the monitoring and implementation of equality laws and multicultural

policies. The term emerges from political and historical (especially

post-colonial) conditions which are remote from Austria. [back

to text]

Images

Hallo Wien: a labyrinth located at the heart

of the Prater, Vienna's permanent funfair (photo:

Anthony Auerbach)

The monsters which advertise the trivial terrors

of the Prater's ghost trains preserve grotesque

anti-Semitic and racist caricatures. (photo:

Anthony Auerbach)

Bei uns in Wien (At

Home in Vienna) by

Klub Zwei, Wittgensteinhaus,

Vienna. (photo: Rainer Egger)

Klub Zwei. In Zusammenarbeit

mit,

installation view, Secession,

Vienna. (photo: Klub Zwei)

Arbeiten gegen Rassismen,

L-R: Anna Kowalska, Klub Zwei/Schwarze Frauen

Community, Klub Zwei, Tramstop, Line D, Vienna.

(photo: D. Koweindl)

Wie Gesellschaft und

Politik ins Bild kommen,

L-R: Klub Zwei/Schwartze Frauen Community, Bureau

d'études, Hans Haacke, Generali Foundation,

Vienna. (photo: Klub Zwei)

|

|

|

|

|

|