|

‘Video needs art history

like a TV set needs a plinth’, session

convened by Anthony Auerbach

for the College Art Association

Annual Conference, Dallas, Texas, 23 February

2008. This session acknowledged video as a disputed,

unstable field and called for

a cross-disciplinary discussion of contemporary

video practice and interpretation: As the traditional

public space of art is increasingly intersected

by its own video-mediations — on

TV, online, by information and

advertising screens, by video

surveillance and the public’s

own portable devices — the challenges

to established relations of representation

become clear. For artists, video

provides no security of artistic

identity and no reliable means of instructing

audiences how to look. For institutions, video

offers new means of communicating with audiences

and monitoring visitors’ behaviour,

but threatens the basic fiction

of the museum: that culture exists

independently of its reproduction.

For art historians, video offers

no surface for inspection, nor

necessarily any depth. Meanwhile,

everyday viewers are highly discriminating interpreters,

continuously decoding the claims of rival channels

and multitudes of screens. While the power of

this technology to propagate

norms is far from exhausted, video practice

continually escapes disciplinary boundaries.

Anthony Auerbach’s introduction to the session and the session programme follow.

I’d like to open this

session by suggesting what I

think is at stake in the proposition, ‘Video

needs art history like a TV set

needs a plinth’. It will

be down to the speakers and our

respondent to interpret it more

concretely, if partially. The

aim of the session is to open

up the territory, but without

universalising it. We should

be prepared to pursue video beyond

the disciplinary boundaries of

art (or art history), not necessarily

to recapture it for art (or art

history), but to chart the relationships

and dependencies between video

practice, video as art-practice,

and the practices of everyday

life, in which we must include

not only the everyday production

and consumption of moving images,

but also the ways in which the

technologies and habits of video

shape subjectivity, identity

and sexuality; experience, perception

and knowledge.

I’d like to open this

session by suggesting what I

think is at stake in the proposition, ‘Video

needs art history like a TV set

needs a plinth’. It will

be down to the speakers and our

respondent to interpret it more

concretely, if partially. The

aim of the session is to open

up the territory, but without

universalising it. We should

be prepared to pursue video beyond

the disciplinary boundaries of

art (or art history), not necessarily

to recapture it for art (or art

history), but to chart the relationships

and dependencies between video

practice, video as art-practice,

and the practices of everyday

life, in which we must include

not only the everyday production

and consumption of moving images,

but also the ways in which the

technologies and habits of video

shape subjectivity, identity

and sexuality; experience, perception

and knowledge.

‘Video needs art history

like a TV set needs a plinth’ is

an ironic statement in so far

as each half of it tells the

truth about the other. That also

makes it a truism. Cleaving an

assertion in two, however, has

the effect of dilating it, suspending

for it a moment, as if pressing

pause and thus raising the possibilities

of review and of play — of

affirmation or contradiction;

reconciliation or critique. The

idea of this session is to use

this pause, this interruption

of the flow, to examine some

of the intersections which could

disclose what I would call the

relations of representation mediated

by video.

In addition to the four speakers

named on the programme I am very

pleased that Jan Hein Hoogstad

has agreed to take the role of

respondent and I trust will help

stimulate and sharpen the discussion

which I would like to open with

you before the session is over.

Angela Harutyunyan’s paper ‘The

Real and/as Representation: TV,

Video and Contemporary Armenian

Art’ examines the meaning

of video art in the context of

the transition from Soviet conditions

to those of independent artistic

production in an independent

Armenia. Whereas formerly, the

self-styled avant-garde had mounted

an underground defence of bourgeois

art against Soviet socialist

realism, the collapse of the

communist regime left artists

exposed to the full force of

global capitalism. The new situation

promised not only international

recognition and the technical

means of achieving it in the

form of consumer electronics,

but also a refuge for a beleaguered

artistic identity.

One might point out — and

it could have been the subject

of another paper — that

by the 1990s, the utopian-narcissistic

drive which had motivated pioneer

video artists and activists in

the United States in the 1970s

was all but exhausted. Those

aspirations, at the time associated

with the left, and supposing

some kind of resistance to the

mass-production (as Chomsky would

say) of consent by monopolistic

media corporations — those

aspirations have, by now been

absorbed into to user-generated

content phenomenon being promoted

by today’s most powerful

advertising and media corporations.

Naima Lowe’s ‘Pushing

Porno’s Buttons: Spectator

Pleasures in Hard-Core Narrative

Pornography’ switches channels

to consider the subject of video

as an active spectator, whose

paradoxically private participation

in mass culture (i.e. the porn

industry) is reflected, and occasionally

mocked, in the narrative premises

of the porn movies themselves.

Here the question is whether

the reflexive devices normally

regarded as the hallmarks of

art — even critical art — are

in fact endemic in video and

indeed in pornography.

Sönke Hallmann — a

theorist with no particular allegiance

to art history — and Karolin

Meunier — an artist whose

performances and video works

frequently puzzle over the debts,

complications and redundancies

which burden and give form to

the communication of identity

and intention — these two

have woven their presentations

together to consider video and

the notion of reading, in particular

the time of reading. Their presentations

hint at a way of reading video

as video, that is to say, hesitating

to apply the patterns of reading

inherited from the reception

of literature, painting or cinema.

Following the presentations we

will hear Jan Hein Hoogstad’s

response which will lead us into

an open discussion (so, please

save your questions and comments).

Jan Hein is a philosopher and

media-theorist with particular

interests in popular culture,

in particular US American Black

music, media technologies and

the figure of the intellectual — which

in his view is as likely to be

an artifact as a person.

A similar line of argument would

suggest that the figure of the

artist is also something produced

rather than necessarily the autonomous

producer of the art work. Accordingly,

the proposal for the session

calls attention to a relationship

between the institutional, disciplinary

and ideological (i.e. cultural)

recognition of a practice — read

art history — and its spatial,

social and concrete supports — that’s

the plinth.

Predictably, the way video tends

to treated in the field of art

is modelled on the way art works

in general are treated. Some

transcendental or essential content

is supposed to be transmitted

by the work even as the object

(the painting, sculpture, text

etc.) is venerated, not to say

fetishised. Even without the

burden of art’s higher

claims, video tends to be regarded

principally as a transmission

medium — with timeshift,

of course — and the emphasis

is on fidelity and transparency:

the reality show. Video appears

to fulfil the promise held out

by the Albertian picture of being

a window on the world, but to

the exclusion of art. Video combines

optics as compelling as those

of a camera obscura, with the

consuming subjectivity of the

bourgeois interior that Walter

Benjamin described as a box in

the theatre of the world.

As we speak today, the box is

beginning to look archaic. The

sculptural potential of the cathode

ray tube set is currently being

revoked by the flat screen, the

biggest consumer electronics

bonanza of all time. The after-image

image of the box is preserved

for the moment in the pleonastic

term ‘flat screen’ which

contains a homage to screens

that were not flat. Nam June

Paik, one of the first to exploit

the potential of the TV set as

sculpture — and its archaic

qualities — famously said ‘I

make technology ridiculous’.

At what point does video return

the compliment to art?

The following papers were heard:

Video Art and the Politics of Representation

in Contemporary Armenian Art

Angela Harutyunyan

Pushing Porno’s Buttons: Spectator Pleasures

in Hard-Core Narrative Pornography

Naima N. Lowe

Reading Video

Sönke Hallmann

Video as Reading

Karolin Meunier

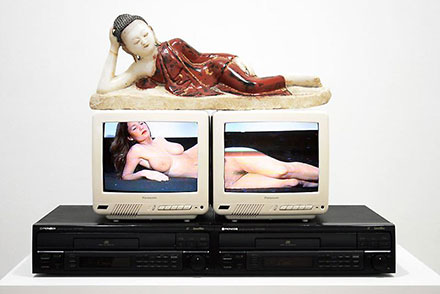

Images

Nam June Paik, Reclining Buddha, 1994, 2 colour televisions, 2 Pioneer laser disk players, 2 original Paik laser discs, found object Buddha, 20 x 24 x 14 ins

...

return: On video ...

return: On video

|