|

|

|

‘Who

is Big Brother? or The Politics

of Looking’ by Anthony Auerbach in Dérive

Zeitschrift für Stadtforschung,

no. 42, January 2011. This article

stems from the project Video

as Urban Condition and explores the intertwining of ‘public’ and ‘private’ space

as well as the subjective complex that binds

together video as spectacle and surveillance.

Amidst the multitude of distractions

offered by contemporary cities,

billboard-sized video screens

are perhaps the most conspicuous

intersections between urban

environments and electronic media. [note

1] The

spectacular intent of such

screens might recommend them

as metonymic images of the ‘media-city’,

but they disclose neither the

nature, nor the meaning of this supposed

hybrid. Urban screens, video

screens, like all screens, are equivocal:

as much as they display, they conceal. From

this double functioning, the repertoire of

urban screening engenders what could legitimately

be called its personae,

whereby a screen appears variously

as if it were the receiver

or the transmitter of images. An urban screen

can, furthermore, appear as the reflector

or the projector of images, while also performing

the functions traditionally ascribed to architecture:

shield, filter, divider, separator. The means

of urban screening thus extend from pixels

to police, concentrating the desires, aspirations

and powers of planners, developers, architects,

broadcasters and advertisers,

among other urban and media ‘players’. Amidst the multitude of distractions

offered by contemporary cities,

billboard-sized video screens

are perhaps the most conspicuous

intersections between urban

environments and electronic media. [note

1] The

spectacular intent of such

screens might recommend them

as metonymic images of the ‘media-city’,

but they disclose neither the

nature, nor the meaning of this supposed

hybrid. Urban screens, video

screens, like all screens, are equivocal:

as much as they display, they conceal. From

this double functioning, the repertoire of

urban screening engenders what could legitimately

be called its personae,

whereby a screen appears variously

as if it were the receiver

or the transmitter of images. An urban screen

can, furthermore, appear as the reflector

or the projector of images, while also performing

the functions traditionally ascribed to architecture:

shield, filter, divider, separator. The means

of urban screening thus extend from pixels

to police, concentrating the desires, aspirations

and powers of planners, developers, architects,

broadcasters and advertisers,

among other urban and media ‘players’.

As long as the effectiveness

of large-scale video screens in urban settings

is unproven — as long, that is, as it

remains difficult to devise measures which would

reconcile the interests of the various parties

involved — the hopes and expectations

invested in ‘urban screens’, hedged

by every precaution that can be mustered by

commercial, political and ideological alliances,

tend to be framed by vague and utopian fantasies.

These fantasies recruit the presumptive universal

mission of art, along with a correspondingly

undifferentiated notion of the public, in support

of potentially conflicting projects. Imagining

urban screens as blank canvasses endowed with

almost limitless potential and believing that,

by placing moving images before a hypothetical

public, giant video screens could, as if by

some kind of cinematic suture, repair the notion

of ‘public space’ (whose demise

is lamented as often as electronic encroachments

on the realm of privacy) clearly moves beyond

the calculations, for instance, of advertisers

who recognise only what can be measured by the

ratio of footfall to eyeballs, [note 2] but would not

like to miss out on the promise of urban screens.

The introduction to the 2007

Urban Screens Conference hailed the ‘discovery’ of

urban screens by the advertising industry, citing

the appearance of outdoor screens in advertisements

aired on television in the role of backdrops

designed to enhance the appeal of soft drinks

and mobile phones (Manchester Urban Screens

Conference 2007). [note 3] However, it should not be

forgotten that the outdoor video screens that

actually exist are most often used by the hardware

manufacturers who install them to advertise

their own range of consumer products — mainly

domestic television sets and mobile phones — and

by media corporations to remind the viewer what

to watch at home. [note 4]

While the evacuation of traditional

communal places has been blamed on the effects

of television, which disbanded and reassembled

the public in their homes, [note 5] the private sphere — traditionally

the patriarchal domain of the bourgeois family — now

tends to be associated with the space of electronic

media. The proliferation of television receivers

and channels within affluent homes, as well

as the use of video rental, home video and video

games, atomised the ‘audience at home’ that

formed television’s public even before

the widespread use of the Internet for information

and entertainment. As the consumption of mass

media becomes the mass consumption of ever more

personalised media, channelled increasingly

via mobile and personal devices, the private

realm (as the space of media consumption) is

no longer confined to the home, but transits

the urban spaces traditionally assumed to be

public. [note 6] As a result, the claim that outdoor

advertising is the ‘last remaining truly

broadcast medium’ is less convincing than

it used to be. [note 7] The incursions, mediated by

video and information technology, of the public

by the private and vice versa tend to complicate

any spatial definition of the two terms to the

point where only a site-specific analysis of

the relations of economic and social power and

privilege could determine precisely how public

and private are intertwined.

Because the phenomena of this

entwining — from video surveillance to

reality TV, from iPhone to YouTube — all

stem from the same set of technologies, focusing

on the ‘forces of production’ is

unlikely to reveal much more than an image of

the technological ‘Great Leap Forward’ already

projected by the suppliers of cameras, displays

and network infrastructures to the consumer

market, public (government) authorities and

commercial property owners alike. More to the

point for an assessment of the traffic in images

would be an analysis of the relations of representation.

Such an analysis would tend to

highlight the distribution of technological

means, and the interpretation of their use,

but would not claim that personal gadgets, CCTV,

video spectaculars or architectural metaphors [note 8]

on their own could make a place public or private,

or determine how visibility or agency are assigned

and maintained in particular urban locations.

In the light of current urban

trends, giant billboard screens might seem anachronistic:

like clumsy replicas of outmoded visions of

the future. [note 9] They might look like attempts at

restoring television to the public places where

it was first demonstrated in the 1920s and 30s,

or perhaps like attempts at reclaiming ‘neglected’ public

places on the model of the post-war living room,

that is to say, making them places where the

modern consumer feels at home. In any case,

urban screens and their paraphernalia cannot

be detached from their historical determinants

any more than they can be isolated from the

regimes of the places where they are installed,

the regimes they are intended both to advertise

(that is, to assert, if not enforce) and to

dissimulate. Such installations remind us that

thinking through video in all its forms in an

urban context — thinking through video

as an urban condition — amounts to a politics

of looking.

*

Yerevan is the capital of Armenia,

a small country with a big past, located in

the southern Caucasus, bordering Turkey, Georgia,

Azerbaijan and Iran. [note 10]

Formerly a land of ancient kings whose territory

reached beyond its present borders, and proud

to be the first nation to adopt Christianity

(at the beginning of the fourth century), in

recent centuries Armenia was under Turkish or

Russian hegemony. In 1922 Armenia was incorporated

into the Soviet Union, and became independent

again in 1991. Nonetheless, the presence of ‘Big Brother Russia’ is

still felt, as it is in many

former Soviet and satellite states.

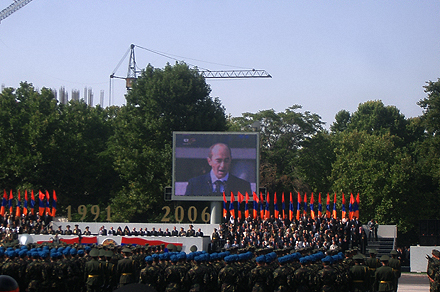

From 2003 until 2007, a large

LED video screen stood on Republic Square in

Yerevan, overlooking the government buildings

and national museums. The square was planned

in the 1920s as part of the principal political

and cultural axis of the Soviet Republic’s

capital city. The spot occupied recently by

the video screen was reserved for a statue of

Lenin. [note 11] The Lenin monument was erected in 1940

and for a time was overshadowed by a really

colossal statue of Stalin which stood on a hillside

above the city. [note 12] Immediately following the

break-up of the Soviet Union, Lenin was removed

from the square that used to bear his name,

and later the pedestal was also demolished.

Angela Harutyunyan suggests that the symbolic

site, left empty, reflected a state of indecision

in Armenian post-independence politics and identity

(Harutyunyan 2008). This indecision was inaugurated

by the brief gesture of ousting the symbol of

the former ruling power and was interrupted

temporarily by the erection of a giant cross:

occasioned by the 1700th anniversary of the

founding of the Armenian Apostolic Church (2001),

but actually supported by a surge in nationalist,

militarist sentiment. The video screen that

took the place of the religious symbol would

appear to reiterate the indecision, and indeed

it performed a variety of functions without

establishing a coherent programme. On anniversary

days it presided over military parades reminiscent

of Soviet times, except that the big screen

now displayed the face of the present leader

(Robert Kocharian, champion of Nagorno-Karabakh

Armenians) in place of the bronze hero of the

Russian revolution. At other times, it displayed

advertisements for real estate developments

and a national promotional video featuring shots

of historic Armenian architecture (including

the buildings of Republic Square itself) and

landscape scenes. Screen time was also rented

out for family celebrations, being used to relay

live video of wedding parades held on the square

in front of the screen.

With that form of display, a

private, commercial transaction on the screen

authorised the occupation of the square in front

of it and underlined the family’s claim

on public space, with the approval of church

and state. While the wedding guests watching

themselves formed the principal audience of

the show, the screening advertised the public

celebration — marriage — which affirms

the regulation of sexual relations and the institution

of the private realm of domestic patriarchy.

*

In George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four

all the functions of command and conscience

usually associated with secular and religious

authorities, as well as all their powers of

inducement and enforcement, converge in the

all-seeing Big Brother, the personification

and ‘embodiment’ of the ruling Party.

Written in 1948, Orwell’s novel projected

a contemporary political parable into the near

future. Clearly, Big Brother is Uncle Joe, and

the book is a bitter reflection on the transformation

of Revolutionary Socialism by Stalinism. Picking

up where Animal Farm left off, Orwell explored

the effects of totalitarian politics. The book

is best remembered for the phrase, ‘Big

Brother is watching you,’ and for the

way Orwell imagined the future ubiquity of television.

In the society Orwell describes,

there is one Party and one TV channel which

is the Party’s principal instrument of

propaganda, projecting the paternalistic gaze

of Big Brother and in his name, continually

announcing the progress of production and of

imperial wars. Except, supposedly, for the space

of the proletarian underclass, and outside the

city limits, the television apparatus is everywhere

and always on. [note 13] The telescreen, as it is called,

is present at home, at work (where it also forms

part of the office machinery) and in the street.

Moreover, it is a two-way device, albeit one-sided. ‘The

telescreen received and transmitted simultaneously.’ (Orwell

1949, p. 4) Thus it also projects the faceless

and menacing gaze of total surveillance. At

any moment, the telescreen might interrupt its

stream of military music and Party announcements

to admonish or instruct an individual. The device

hears everything, even a heartbeat, but no one

speaks to the screen.

As it turned out, this kind of

technical apparatus of surveillance and control

was not installed under the actually existing

regimes Orwell indicted as travesties of Socialism,

and against whose threats to individual liberty

he intended to warn. Instead, television entered

every home as the favourite propaganda instrument

of the consumer society and the installation

of video surveillance propagated the fear (and

the love) of Big Brother in affluent, capitalist

democracies.

Noam Chomsky famously drew attention

to the totalitarian aspects of capitalism under

the rubric Manufacturing

Consent (Chomsky and

Herman 1988). The title of Chomsky and Herman’s

critique of mass media is an ironic homage to

the political commentator Walter Lippmann, whose

Public Opinion identified propaganda — ‘the

manufacture of consent’ — as an

essential component of democratic government

(Lippmann 1922). For Lippmann, modernity promised

the demystification of ‘public opinion’ along

with great technical improvements in the art

of persuasion, and indeed good government, provided

the instruments were entrusted to the right

people. ‘The Engineering of Consent’ proposed

by Edward Bernays (Bernays 1947) extended Lippmann’s

industrial metaphor and defined the role of

the propagandist — the ‘publicity

man’ [note 14] or ‘public relations counsel’ (as

Bernays styled himself) — in the division

of labour. The specialist knowledge and technical

authority of the engineer is thus interposed

between the ruling class and the public as between

the directors and the management of an industrial

concern. According to the theory of engineering

consent, the mass production of opinion in a

democracy is mediated by an educated class of

bureaucrats, managers, teachers, journalists

and the like who form public opinion. It is

they whose thoughts are to be shaped, just as

in Orwell’s novel it is the class of Party

functionaries, bureaucrats and the like — the ‘Outer

Party’ to which the book’s hero

belongs [note 15] — who are haunted by telescreens,

not the mass of ‘Proles’ who are

considered by the Party incapable of thought

and so of little concern to the ‘Thought

Police’.

As the publicist switches from

political to commercial concerns, the qualification

of the public is extended only to those capable

of responding economically to the profit of

the publicist’s client. For commercial

media such as advertising-funded television

channels, political and commercial concerns

are identical. The population that fails to

qualify economically as the public is thus excluded

from representation by the media whose business

it is to reflect its public’s interests

(which is not the same as ‘the public

interest’ — as has often been pointed

out when the latter has been invoked to justify

intrusions on privacy by journalists).

In Chomsky’s analysis of the mass media,

in particular the press and network television

in the United States, the ‘propaganda

model’ reappeared as a scandal. The defenders

of the media institutions Chomsky accused of

complicity in America’s foreign policy

atrocities, however, could easily counter his

allegations by citing Orwell’s dystopia

as the fate Americans were spared thanks to

the free press. Moreover, Chomsky’s interventions

were ridiculed as conspiracy theories as fantastic

as any fabricated by the Party in Nineteen Eighty-Four. [note 16]

The system of production Chomsky

described was certainly paternalistic and exerted

powerful influence over the flow of information,

the mobilisation of desire and the conformity

of behaviour. But it was not quite Big Brother.

To be fair to Orwell, the regime

of the telescreen is a fable, an allegory of

a political condition more than a technological

prediction. Nonetheless the undisguised parallels

with the Soviet Union under Stalin and the persistence

of the language Orwell invented for the imagined

Ingsoc (English Socialism) — the code

of its regime — invite historical comparisons.

So it would be worth considering for a moment

how television and surveillance were implemented

under Communism.

Although the isolated, passive

and unsupervised character of home viewing was

at first regarded with some suspicion by the

Soviet establishment, television was not neglected

as a means of popular instruction and entertainment.

Its value was perceived at least as a counter-measure

to Western radio propaganda and as a sign that

Socialism could provide everything that modern

technology promised. Thus provision was made

in the economic plan (though it could have been

dictated otherwise) for the development of domestic

television on a model in some respects similar

to that adopted in the West. Television was

enthusiastically welcomed by Soviet viewers

in their homes despite the notoriously unreliable

equipment and often dismal programmes (Roth-Ey

2007).

Surveillance, on the other hand,

was instituted before the television era and

did not rely on technology, but mainly on human

resources mobilised by ordinary incentives such

as material rewards and credible threats. The

effectiveness of surveillance, as a means of

projecting power and exercising control over

the Soviet public, stemmed from its boundlessness.

Since the defence of the revolution and the

security of the state were perceived as identical,

the security apparatus instituted by Lenin recognised

neither national borders nor any legal constraint

on its activities. The same organisation was

charged with suppressing dissent within the

Party and revolt within the populace; it was

responsible for domestic surveillance, foreign

espionage and counter-espionage; for internal

security and the pacification of an empire.

The vigilance of the state was not delimited

by any boundary that would mark the external,

or the private. Neither was there any boundary

between police procedure and political terror.

Orwell showed vividly what happens to the character

of information in circumstances like these.

In the Soviet Union, the recruitment

of informers and the flow of information were

facilitated by the state’s involvement

in nearly every aspect of daily life, from social

organisations and structures to employment,

housing and supply. Big Brother might be the

metaphor for a remote, watchful authority, but

was actually present in the eyes and ears of

intimates, colleagues, friends and family.

*

Video and electronic surveillance

networks are an increasingly pervasive feature

of contemporary urban life, although without

the centralised system of propaganda and monitoring

which characterised the regime of Big Brother.

The proliferation of the technical apparatus — cameras,

monitors, recording, transmitting and receiving

devices — combined with a weak regulatory

apparatus has raised a multitude

of possibilities and fears. [note

17 ]

Popular fiction suggests how

the allure of the possibilities is as much part

of the fantasy of surveillance as is the fear

of it. In the movies, any camera installed openly

for supposedly innocuous reasons could be being

monitored and directly controlled by ultra-secret

government agencies. [note 18] The secret agents, moreover,

possess technology that can unveil a wealth

of detail normally masked by the low-resolution

pictures which signify surveillance — that

is, the image quality that distinguishes surveillance

from other video genres. The facilities for

intercepting communications that the fictional

agents are supposed to have in the same movies

might in fact be closer to real surveillance

fantasies, such as the United States’ TIA

(Total Information Awareness) and related programmes, [note 19]

than Hollywood’s secret CCTV networks

and astonishing image enhancements are to the

current state of the art in video surveillance

technology.

However, even if the technical

possibilities are assumed to be expanding, and

becoming ever more widely distributed, the fantasy

of surveillance — if it is not to run

into its own contradictions — continues

to run ahead of the fulfilment promised by each

technological development. Video surveillance

installations configure the fears and desires

to which they owe their rise. Those fears and

desires are in turn propagated, and multiplied

as surveillance gives rise to other fears and

more desires. Unifying this multiplicity, reconciling

its contradictions, is not a matter of technology — notwithstanding

the seductiveness of the idea of a big screen

capable of binding a crowd the way the small

screen bound the audience at home.

While technology may seem universal

or indifferent, the meaning and potential of

video/surveillance depends on who and where

you are, and will change as you move from one

urban situation to another. Furthermore, video/surveillance

determines who you are in a given place, that

is to say: the configuration of video/surveillance

determines who watches and who is watched, what

is seen and what is shown. The configuration

therefore amounts not only to an instrument

of looking but also articulates relations of

representation which must be understood not

only in the technical sense (how and when what

or who is visible to whom), but also in the

political sense. Compare, for example, what

the possibilities of video/surveillance might

suggest to a democratic government anxious both

to highlight the threat of terrorism and to

reassure the public, or to an authoritarian

government concerned about the subversion of

media controls; to an advertising agency or

retail enterprise eager to identify and target

customers more precisely, or to the people employed

to watch for the customers who don’t pay;

to a social housing tenant worried about anti-social

behaviour in the neighbourhood or to someone

more interested in online social networking;

to a privileged citizen, confident of his/her

rights, concerned with privacy, [note 20] or to a homeless

person.

*

Since 1999, when the popular

TV series was first aired in the Netherlands,

the name Big Brother has been associated with

what is known as reality TV. In the Big Brother

game show, members of the public voluntarily

submit to total surveillance, which is transmitted

in regular TV digests, as well as live streams

on cable and online, for the audience to observe

and judge the contestants’ behaviour.

The contestants trade their temporary isolation

and subjection to the regime of the observer

(more or less mediated by the producers of the

show) for the promise of fame (even if only

for fifteen minutes) and the possibility of

a cash prize. The producers discovered a means

of attracting large audiences without having

to hire expensive professional talent and a

way of observing their audience directly via

the ‘interactive’ tie-ins associated

with the series. [note 21]

The viewer’s motivation is not so obvious.

Why should Big Brother’s promise of reality

be more compelling than fictional drama? How

does watching the ‘housemates’ confined

to the Big Brother set conform with the escapist

model of popular entertainment? How does the

audience identify with the housemates? If the

Big Brother contestant is already ‘one

of us’, what aspirations does the show

mobilise? What wishes can it fulfil?

The appeal of Big Brother is

probably the same as the fascination of television — that

is to say, seeing at a distance: the binding

of the viewer to a distant object. The pleasure

this fascination offers, in the context of broadcast

TV and closed circuits, is voyeuristic. Video

(Latin: I see), literally, identifies the subject

as the one who looks.

In the early days of television,

before videotape, stations used to broadcast

live pictures from distant cities to fill the

gaps between programmes. Apparently, these shows

were quite popular, although they had no content

and no message other than demonstrating the

ability of television at the same time to assert

the remoteness of the object and insert it in

the domain of the viewer. There, in television’s

unrecorded stream, the object is only to be

watched, but doesn’t coalesce into an

image that will yield to desire: an image that

could be had. For the voyeuristic subject, the

object is always remote. Video recording plays

back only the succession of incomplete images,

each fraction only anticipating the next, but

never adding up (Cubitt 1991, p. 30). Slow motion

replay seems only to dilate the anxiety of the

moment, while it steals simultaneity. Under

inspection, the video image vanishes in lines

and pixels. [note 22] No image stands for the object-out-of-reach

unless it is an image-out-of-reach. Thus desire

is focused not on an object or on an image,

but on the act of looking, and is fetishised

in the apparatus of looking.

The notion of fetish doesn’t quite explain,

but hints at a way of understanding some of

the seemingly irrational behaviours associated

with video: behaviours displayed, for example,

by people who point their camcorders but don’t

shoot, who record TV shows but never watch them,

who attend live events only to watch them on

video screens, and who appear in various ways

to revere the TV set.

But to return to the question

of Big Brother, I would like to consider some

seemingly irrational aspects of video surveillance.

Although the commonplace rationale of video

surveillance — its ‘ideology’ as

John McGrath calls it (McGrath 2003) [note 23] — is

crime prevention, the effect of video surveillance

on crime rates has been shown to be mostly insignificant. [note 24]

The CCTV images provided regularly to the broadcast

media, with the aim of helping to solve crimes

that they clearly did not prevent, nonetheless

support the ideology of surveillance and, moreover,

legitimise the pleasures of viewing. The videos

broadcast by programmes such as Crimewatch UK

or on the news are to some extent selected and

qualified by the standards of television entertainment.

Thus the videos of people being victimised are

accompanied by warnings of ‘scenes of

a graphic nature’ or ‘scenes of

violence’ and solemn appeals for information.

However, they are not really different from

surveillance videos, which circulate only for

their gossip and amusement value, if not for

the explicitly voyeuristic enjoyment of sex

and violence.

While video surveillance appears

to have little influence on criminal behaviour

(despite offering criminals a chance of appearing

on television), it is said to have an influence

on behaviour that may be a nuisance, but would

not ordinarily appear in the public record as

a crime statistic (dropping litter, or urinating

in the street, for instance). This claim, which

is harder to substantiate or to disprove, [note 25]

along with the assertion that CCTV makes people ‘feel

safe’, comes to replace the primary ideological

justification, but may still mask other objectives.

As if in anticipation of any critical assessment

of the effectiveness of video surveillance,

it is simply asserted that CCTV is a ‘good

thing’ [note 26] whose potential would be unlocked,

if not by the technical improvements promised

by the next generation of equipment, then by

consciousness raising. A local authority select

committee report on the effectiveness of CCTV

came to the confident conclusion: ‘Increase

public awareness of the existence and effectiveness

of CCTV in the borough. This will lead to an

added sense of security to the public and act

as a deterrent to the criminal fraternity.’ (Aldred

2005, p. 37) This statement suggests how surveillance

and propaganda might be bound together in a

manner worthy of Big Brother. It suggests how,

given an ingenious combination of technology

and information, consciousness will divide the

public from the ‘criminal fraternity’.

The attempts by privacy campaigners,

activists, artists and pranksters to raise awareness

of surveillance tend to be frustrated by the

already high levels of public awareness of CCTV

(since the systems are designed to be conspicuous) [note 27]

and widespread acceptance, even enthusiasm for

it, which is reflected in the wider commercial

and cultural exploitation of the same technologies.

This delight in surveillance seems to persist

despite growing popular scepticism of the primary

public justifications of mass-surveillance infrastructures.

Consumer-electronic fetish objects, popular

shows such as Big Brother, spy thrillers, as

well as the exploits of campaigners, activists,

artists and pranksters, tend to highlight the

ludic and voyeuristic pleasures of surveillance,

while providing a different ideological screen

for the viewer — not the supervising authority,

but the player, the connoisseur of cultural

appropriations of technology, the autonomous

subject, author, if not of its own destiny,

at least of its spare time. Culture too is widely

assumed to be a ‘good thing’ and

accordingly claims a leading role on the urban

scene, assisting in the formation of consciousness

and hence in the identification of the ‘public’ and

the exclusion of others.

*

When, in the mid-1970s, Rosalind

Krauss said, ‘The medium of video is narcissism,’ she

aimed to bring an emergent genre of art into

critical focus by isolating it from its technological

base, and comparing it to established modes

of art production (Krauss 1976, p. 50). At the

time, video art was even more remote from the

mass media than other forms of contemporary

art and owed its recent rise to the commercial

availability (since the late 1960s) of portable

video equipment, which had originally been developed

for surveillance. The machines were still much

better adapted to this purpose than they were

to anything resembling broadcast television

and lent themselves to closed circuits and feedback

loops, to the staging of the author/looker as

simultaneously desiring subject and desired

object. Krauss’ commentary suggests narcissism

is a dead end for art and video is somehow destined

to engulf artists in their own vanity. [note 28] This

might not be borne out by the subsequent history

of video art, but it is clear from contemporary

cities that narcissism flourishes in an environment

of closed circuits, video loops, displacements

and feedback. The proposition that narcissism

(Narcissus’ morbid fascination with his

own reflection) is the stuff of which video

is made (like clay is the medium of sculpture)

suggests a libidinal charge to the compelling

presence of video which might be more than metaphorical.

The audience assembled by the Manchester Big

Screen — a 25-square-metre outdoor screen

in the city centre, run by the BBC as part of

its Public Space Broadcasting project — was

called narcissistic by the Chief Project Manager [note 29]

not only because of the popularity of local-interest

programming. No bigger cheer went up from the

crowd than when the cameras turned on the audience

and the screen switched from projector to reflector.

CCTV is not always as spectacular as this, but

the narcissistic moment is no less enmeshed

in the urban screens woven by surveillance.

The monitor positioned at the entrance to a

place, which announces ‘You are being

watched’, unites the discriminatory and

the propaganda functions of surveillance by

staging the division between people who are

welcome in the place and those who are not,

as a moment of self-regard.

The location merges the video

stream with the stream of people crossing the

threshold of the place. The image crosses the

voyeuristic pleasure of television with narcissistic

desire, seducing you with the unattainable object

of desire — yourself — captured

where you stand — at a distance. The monitor

entwines identification with the watcher and

identification with the watched even more tightly

than watching Big Brother on broadcast TV. Recognising

one’s own image on screen affirms both

identifications, while dissimulating the actual

regime of the place with the comforting reassurance

of the sign on a map, which says ‘You

are here.’

Images

Republic Square, Yerevan,

Armenia: by Anthony Auerbach, Adam

Lederer

Notes

- The television towers, which stand out on many a city’s skyline, remain as monuments to broadcasting while TV transmission has gone underground, extraterrestrial and over IP. [back to text]

- In the industry jargon, ‘eyeballs’ means individual viewers of an advertisement, ‘footfall’ means pedestrian traffic in retail environments. [back to text]

- The first Urban Screens Conference took place in Amsterdam in 2005. Subtitled ‘Discovering the potential of outdoor screens for urban society’, the first edition welcomed a wide range of speakers to discuss the uses of large-scale LED screens in urban settings. In the words of the organisers, the conference would ‘investigate how the currently dominating commercial use of these screens can be broadened and culturally curated. Can these screens become a tool to contribute to a lively urban society, involving its audience interactively?’ Contributions from academics, curators and artists were complemented by talks by architects, technology providers, advertising agencies and broadcasters. See Auerbach, Anthony (2006): Interpreting Urban Screens in First Monday, Special Issue 4. [back to text]

- Digital billboards, run by the major outdoor advertising agencies, displaying a succession of static advertisements are becoming a more common sight. These installations allow the agencies to sell the same location to multiple advertisers while avoiding the costs of printing and putting up traditional posters. Furthermore, by segmenting ‘airtime’ outdoors, the system allows advertisers to target different ‘audiences’ with different messages at different times of the day. As the ability of the agencies to ‘deliver audiences’ (see note 7, below) depends on site-specific analysis of urban traffic, so ever more discriminating surveillance of ‘public’ space is incorporated by market research. [back to text]

- The disuse of traditional communal

places such as town squares, suburban high streets,

churches and cinemas has often been followed by their

occupation by non-traditional communities such as

teenagers, immigrants and, in some places, Protestants:

nearly all the grand city-centre cinemas in São Paolo,

Brazil, the world’s largest Catholic nation,

are now occupied by evangelical churches (if they

do not survive as pornographic cinemas). [back

to text]

- The notion of privacy as a ‘right’ is invoked, in particular, in connection with the trade in data gleaned from individuals’ online and urban trajectories, their networking, consuming and viewing habits. While concern is expressed about the technologies that would strip individuals in public places of the anonymity that used to be afforded by the modern city — that camouflage which preserved the ‘private’ individual immersed in a crowd — the owners of cars, credit cards, smart phones and access privileges still demand protection from criminals, and worse, terrorists. This ‘right’, then, is the right of some people, but not others, to be private in public. [back to text]

- The statement is from ClearChannel’s ‘Glossary’, 2005. The same agency’s 2009 marketing material claims: ‘... instead of delivering panels, we deliver audiences. Outdoor is often described as the last broadcast medium and while this is still true, developments in campaign planning have meant that we are now able to deliver different consumer groups with more accuracy than ever before — including different socio-demographic groups, ethnic audiences and “tribes”.’ ClearChannel Outdoor (2009): Audience Solutions. [back to text]

- A ‘spectacular’ (noun) is the term coined for high-profile electrified advertisements such as are associated with Times Square, New York, and Piccadilly Circus, London. The Times Square Alliance, formed in 1992 to promote ‘economic development and public improvements’ in the area, uses the metaphor ‘The Crossroads of the World’ as its slogan. ‘Forum’ and ‘Agora’ are popular names for shopping centres. [back to text]

- The cityscape of Los Angeles, 2019, in Ridley Scott’s Blade

Runner (1982) is one of the most often cited. However, outdoor video screens were imagined even a century earlier, when television was little more than a hypothetical possibility. In Albert Robida’s Le

vingtième siècle (1882) the streets of Paris, 1952, are equipped with giant public ‘téléphonoscopes’ run by the global media corporation L’Époque. [back to text]

- The present essay stems from a talk I gave in Yerevan in 2006, hosted by the Armenian Center for Contemporary Experimental Art as part of the project Video as Urban Condition. The content received additional grafts in the course of the seminar I devised for the International Summer School for Art Curators, Post

Socialism and Media Transformations: Strategies

of Representation, Yerevan, 2008. [back to text]

- According to a Soviet-era tourist guide, ‘This is the centre of Yerevan, where ceremonies and meetings are held and through which processions pass on highdays and holidays. The statue of Lenin, the work of Sergei Merkurov (1881–1952), a prominent Soviet sculptor, rises high over the southern part of the oval square. This skilfully executed image of the leader, philosopher and revolutionary spokesman is extremely impressive. The restrained movement of the hand, the slight inclination forward, as if taking a step into the future, give the sculpture a sense of purpose and movement.’ (Transcribed by Raffi Kojian) [back to text]

- The Stalin statue was part of a war memorial erected after 1945. It was removed after 1953 and later replaced by an equally colossal statue of Mother Armenia, which remains in situ. The army museum housed in the pedestal of the monument is now mainly dedicated to the post-independence conflict with Azerbaijan over the Nagorno-Karabakh region. [back to text]

- For the protagonist of the story, the supposition, fatefully, turns out to be wrong. [back to text]

- ‘The development of the publicity man is a clear sign that the facts of modern life do not spontaneously take a shape in which they can be known. They must be given a shape by somebody, and since in the daily routine reporters cannot give a shape to facts, and since there is little disinterested organization of intelligence, the need for some formulation is being met by the interested parties’. Lippmann, Walter (1922): Public Opinion. London: Allen & Unwin, 345. [back to text]

- Winston Smith is, after all, a kind of journalist. His job is ‘correcting’ the historical record in accordance with the Party’s directives, removing ‘unpersons’ from back issues of The Times, for example, rewriting the articles, altering the photographs. [back to text]

- In Orwell’s book, a shadowy Brotherhood of conspirators is rumoured to be behind every plot foiled by the loyal organs of the Party. The captured plotters confess their secret association with the arch Enemy of the People, Emmanuel Goldstein, and duly submit to the Party’s retribution. [back to text]

- An overview was sought by the UK House of Lords Select Committee on the Constitution (2009) Surveillance: Citizens and the State. London: The Stationery Office. [back to text]

- For instance: the popular thriller The Bourne Ultimatum, directed by Paul Greengrass (2007), which is noted for its ‘realism’; or Enemy of the State, directed by Tony Scott (1998), where the heroes defend their individual morality and privacy with the same surveillance technologies used against them by the corrupt agents of the state. The End of Violence, directed by Wim Wenders (1997) inserts the fantasy of surveillance into the heart of the ‘dream factory’, with the secret control room of a sinister surveillance system concealed in Los Angeles’ Griffith Observatory, overlooking Hollywood itself. [back to text]

- For example ADVISE (Analysis, Dissemination, Visualization, Insight, and Semantic Enhancement), or PSP (Presidential Surveillance Program). Such programmes have been mocked as fantasies: the ‘Big Database in the Sky, the database that knows everything about everyone and can tell who’s been naughty and who's been nice’. Stokes, Jon (2006): Revenge of the Return of the Son of TIA, Part LXVII. [back to text]

- Privileged citizens such as the Surveillance Camera Players who performed an adaptation of Nineteen Eighty-Four in the New York Subway for the cameras, for passers-by and ultimately for YouTube (Surveillance Camera Players (1998): Surveillance Camera Players Do George Orwell’s 1984; or the author of a movie — and by law the protagonist — who exploited a provision of the UK Data Protection Act which requires corporations to supply copies of personal data including surveillance video to an individual who requests it. The masking of faces required by the same law to protect the privacy of other individuals visible in the video prompted a science fiction-inspired story of redemption through narcissism (Luksch, Manu (2007): Faceless). [back to text]

- See Andrejevic, Mark (2003): Reality TV: The Work of Being Watched. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. [back to text]

- The title sequence of Zidane: A 21st Century Portrait, directed by Douglas Gordon and Philippe Parreno (2006), stages that frustration as the prelude to a film that is nothing other than voyeuristic. [back to text]

- Like most commentators, McGrath speaks mainly of surveillance systems installed by public authorities democratically accountable for their actions and policies and hence required to formulate an ideology. Early and widespread implementation of CCTV by local authorities in the UK has also provided a base for the assessment of its effects. Privately installed surveillance systems mainly escape regulation and analysis. [back to text]

- See Gill, Martin and Spriggs, Angela (2005): Assessing the impact of CCTV. London: Home Office Research, Development and Statistics Directorate. Gill and Spriggs’ Home Office Research Study points out that the effect of video surveillance on specific crimes in specific areas such as ‘vehicle crime’ in car parks was noticeable, but difficult to separate from ‘confounding factors’ such as improved lighting introduced at the same time as video surveillance for the same purpose. In these cases the displacement of crimes to neighbouring areas not under surveillance was also more noticeable. In most other cases, statistically significant changes in crime rates resulting from the installation of CCTV could not be demonstrated. [back to text]

- On this score, the effects of video surveillance installations are not compared with the effects, for example, of providing waste bins or public toilets, which, if installed, would doubtless have to be under video surveillance to prevent misuse. In many places, public toilets were closed because they were being misused by homosexuals or drug users. In the UK, waste bins were removed from public places because they might have been used by terrorists to hide bombs. [back to text]

- ‘First, CCTV was credited with the well-reported arrests of the murderers of James Bulger in 1993, and later of the Brixton nail-bomber in 1999, leading to a universal assumption that CCTV was “a good thing”. This lessened the need for project planners to demand evidence to support the claims made for CCTV. There was also little need to think about whether CCTV was the best measure to address the particular problems in the area where it was to be applied. One project manager stated: I’m all for [more cameras]; it builds the system up doesn’t it? If I had my way I’d have cameras everywhere, ’cause they’re good. The Home Office endorsement of CCTV further diminished the need for planners to be seen to assess CCTV critically, as one of many possible crime reduction initiatives.’ Assessing the impact of CCTV, 63–64. [back to text]

- The soundtrack of Surveillance Camera Players’ video documentation of their performance of Nineteen Eighty-Four is interrupted by a conversation between the Players’ lookout, who was also recording a CCTV monitor, and a passer-by who was wondering what was going on. When it is explained that the aim of the show is to draw attention to ‘surveillance cameras all around’, he replies, ‘Yeah, but who doesn’t know that?’ [back to text]

- On Freud’s authority, narcissism signifies an incurable perversion of the reflexiveness Krauss had learned to expect from art. [back to text]

- Mike Gibbons, Project Manager, BBC Live Events, during the Urban Screens Conference, 2005. Manchester was the pilot for a network of city-centre ‘Big Screens’ run by the BBC in collaboration with the technology providers Philips, commercial sponsors and local authorities. The BBC provides continuous programming with sound, day and night, without commercial interruptions. The screens provide, among other things, opportunities for communal viewing of live TV, lunchtime entertainment, local news, opportunities for screening selected art works or amateur videos, as well as backdrops for events and celebrations. Their value is measured in terms of the ‘regeneration’ of public space — normally as retail and leisure space. [back to text]

References

Aldred, Mark, Select Committee no. 3 (2005): The

Effectiveness of CCTV within the Wigan Borough. Wigan:

Wigan Borough.

Andrejevic, Mark (2003): Reality

TV: The Work of Being Watched. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Auerbach,

Anthony (2006): Interpreting Urban Screens. In: First

Monday, Special Issue 4

Bernays, Edward L. (1947):

The Engineering of Consent. In: Annals of the American

Academy of Political and Social Science, 250, 113–20.

Chomsky, Noam and Herman, Edward S. (1988): Manufacturing

Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media.

New York: Pantheon Books.

ClearChannel Outdoor (2009): Audience

Solutions.

Cubitt, Sean (1991): Timeshift:

On Video Culture. London: Routledge.

Gill, Martin and Spriggs, Angela (2005): Assessing

the impact of CCTV. London: Home Office Research,

Development and Statistics Directorate.

Gordon, Douglas and Parreno, Philippe (2006): Zidane:

A 21st Century Portrait.

Greengrass, Paul (2007): The

Bourne Ultimatum.

Harutyunyan,

Angela (2008): State Icons and Narratives in the

Symbolic Cityscape of Yerevan. In: Harutyunyan, Angela,

Hörschelmann, Kathrin and Miles, Malcolm (Ed.): Public

Spheres after Socialism. Bristol: Intellect

Books. 21–30.

House of Lords Select Committee on the Constitution

(2009): Surveillance: Citizens

and the State. London:

The Stationery Office.

Krauss, Rosalind (1976): Video: The Aesthetics of

Narcissism. In: October, 1, 50–64.

Lippmann, Walter (1922): Public

Opinion. London:

Allen & Unwin.

Luksch, Manu (2007): Faceless.

Manchester Urban Screens Conference (2007): A

Media World in Flux.

McGrath, John (2003): Loving

Big Brother: Performance, Privacy and Surveillance

Space. London: Routledge.

Orwell, George (1949): Nineteen

Eighty-Four. London: Secker & Warburg.

Robida, Albert (1882): Le

vingtième siècle. Paris: Decaux.

Roth-Ey, Kristin (2007):

Finding a Home for Television in the USSR, 1950–1970.

In: Slavic

Review, 66, 2,

278–306.

Scott, Ridley (1982): Blade

Runner.

Scott, Tony (1998): Enemy

of the State.

Stokes, Jon (2006): Revenge of the Return of the

Son of TIA, Part LXVII.

Surveillance Camera Players (1998): Surveillance

Camera Players Do George Orwell’s 1984. Video.

Wenders, Wim (1997): The

End of Violence.

|

|

|

|

|

|