|

|

|

‘The

Migrating Monument’, Tom Vandeputte

in conversation with Anthony

Auerbach, in Supplement

Material, edited by Caspar Frenken and

Tom Vandeputte, Rotterdam/London:

Perhaps (Perhaps), 2010. A discussion on architecture,

anxiety and monumentality after

Aerial Reconnaissance

Berlin.

TVDP: Aerial

Reconnaissance Berlin documents

series of ‘low altitude aerial surveys’ you

did as part of the International

Necronautical Society (INS) ‘Inspectorate’.

Where does the preoccupation with this aerial

surveys come from?

AA: That would be very

low altitude aerial

surveys. My first expedition

of this type was an aerial survey

of the carpet in my studio, done

from a height of about 90 centimetres.

I’d

worked for years in that studio

on drawings. They had gradually

become more and more intense,

complicated, and, in the end

unmanageable, partly as a result

of what you might call centrifugal

tendencies — an

interest in architecture, landscape

and cartography, that eventually

drove me out of the studio — and

partly as a result of allowing

the space of drawing to be infiltrated

by other spaces — like

that of games, maps and so on.

There was one piece that got

quite out of hand, so I resorted

to subdividing a grid that was

already part of the structure

of the drawing and notating it,

making a map of the drawing in

81 parts, encoding the ‘topography’ of

the drawing like a map encodes

a landscape. That way I hoped

I’d be able

to discard the original drawing.

The aerial survey came about

from the wish to turn the practice

of drawing ninety degrees. So

instead of recording something

in some system of marks and traces

in the vertical plane — a

picture, I turned my attention

to recording the marks and traces

that might remain of the practice

of drawing — on

my carpet. An aerial survey is

series of overlapping vertical

photographs that covers the whole

terrain. I realised that an aerial

survey, examining a surface,

moving rhythmically back and

forth across it, implies a notion

of reading. That idea of reading,

reading material, was what I

brought to the Berlin project.

TVDP: The locations you surveyed in Berlin

are described as ‘sites of erasure’.

What do you mean by that?

AA: Whereas the sites I surveyed in the context

of my own practice were more or less accidental

or biographical, the INS’s ‘central

concerns’ suggested criteria for the selection

of sites for inspection that could be formulated

precisely: ‘locations where no trace can

be found of incidents or persons of interest

to the INS; where there is evidence of attempts

to cover or erase the traces of incidents or

persons; where there is evidence of attempts

to conceal the erasure.’

That sounds like a contradiction of a method — aerial

photography — that’s supposed to

be all about registering traces. But why not

record erasure, or whatever is written over

erasure? It’s often said of cities, Berlin

included, that they are like palimpsests. To

me, this always seemed a rather sentimental

notion, presupposing that the text, once erased

and overwritten, could be recovered: made legible

again if one only could inspect it closely enough,

or, presupposing at least that the obscure remnants

of erasure and inscription — the present

state of the surface — will stand in for

this promise of legibility. I’m all for

letting a look — inspection — arouse

such desires, but the point in Berlin was to

examine surfaces where there really is no trace

of any ‘original’ mark or inscription,

and to let the material complicate the method.

Finding such sites in Berlin is not difficult

if one considers the places of the most intense,

most intentional and ruthless erasure tend to

be those sites that have been memorialised or

monumentalised in various ways. Berlin, the

city the INS has designated the World Capital

of Death, exhibits an unusual abundance of such

places.

That line of investigations has led me to think

quite a lot about monuments — and monumentality,

so I was interested in your approach. How do

you identify a monument?

TVDP: In our project we talked a lot about

the notion of monumentality as distinct from

monuments. The term monumentality seems to suggests

the effect, disconnected from the object. For

example, scale is a property that seems to stick

stubbornly to whatever we conceive of as monumental.

AA: Do you mean size? Monumental means big.

Monuments are supposed to look like they are

not going to move, therefore should be very

heavy, and to look heavy, they should be big,

shouldn’t they. I would put the emphasis

on seeming immobile — though in fact monuments

often migrate. A thing called the ‘Schwerbelastungskörper’ [heavy

burden body] in Berlin could be embodiment of

monumentality in its pure form. It’s a

large concrete cylinder built for no other reason

than to be very heavy, and it has no other inscription

than ‘Denkmal’ [monument] since

it is a protected building and has recently

been restored. Although it’s indestructible,

it became dilapidated. The object was originally

built to test the foundation system for the

colossal architecture of the ‘Welthauptstadt’ [world

capital] that Hitler and Speer imagined; it

is a monument to a failed utopia, albeit a Nazi

utopia.

TVDP: We like to think of it in terms of scale,

because it seems possible to understand this

traditional aspect of monumentality in terms

other than its physical dimensions. Attention

seems to be a concept which allows us to re-conceptualise

this aspect of monumentality: eventually, monuments

need to attract attention in one way or the

other.

AA: One way or another. Recently, I came across

an advertising agency whose specialty is what

they call ‘monument veiling’. If

a monument is being restored or redeveloped,

they will dress the scaffolding with monumental

advertising posters. They offer brand-owners

building-sized advertising opportunities in

prominent locations, and monument-owners revenues

to support redevelopment. If the client monument

doesn’t need the money, or the agency

can’t sell the space, they make replica

façades — a simulation, an idealisation,

one might say, of the monument that is for the

moment hidden by this very simulation. In Berlin,

they also provide replica façades for

monuments that don’t exist anymore, or,

as the sponsors of the such façades would

wish: don’t yet exist again. In any case,

it looks as if monumentality and advertising

are engaged on the same territory in the battle

for eyeballs.

TVDP: Debord considered monuments as part of

the society of spectacle. There is an interesting

part in his technical notes to the films he

made in the late 1950s. Some of these films

document the situationists’ ‘dérives’ through

Paris. In the notes on ‘On the Passage

of a Few Persons Through a Rather Brief Unity

of Time’ Debord remarks that, whenever

the camera would risk filming a monument, they

would shoot the scene from the opposite direction:

that is, from the point of view of the monument.

In our project, we have appropriated this idea

and extended it: we have made a photographic

documentation of the city of Rotterdam, shot

through the eyes of monumental statues: Erasmus,

Pim Fortuyn, Hugo de Groot, Monsieur Jacques

... The view of each statue produces a double

image: it consists of two photographs, documenting

the statues' perspective through both of their

eyes, together forming a stereographic image.

We liked how it appears as a necessarily futile

attempt to revive these figures of the past;

to engage with the issue of personification;

and of course to work with the idea of the collection

of monuments as a representation of a city's

historical conscience.

AA: The thing you really pick up on in your

project isn’t so much the ‘spectacle’ and

Debord’s aim, somehow to suppress it by

not picturing monuments — I imagine that

would only make their presence

only more palpable, and would

set up quite a complicated protocol for a dérive

in a place like Paris ... what you pick up on

is a connection between monumentality and surveillance.

Debord’s

prohibition on the spectacular

aspect of monuments brings him

to inhabit their gaze. You do that literally,

in order to view the city through the eyes of

a monument. I suppose the question that arises

then is: What kind of subjectivity a monument

would have — and

how that subjectivity is mediated

by a look. Clearly, a monument that presumes

to admonish the public in the name of the dead,

like a system of surveillance, a monument stands

in for a super-ego (like you say, the conscience)

that should somehow moderate the behaviour of

the people affected by it.

TVDP: I am interested in the persistent fantasy

that we are being watched by monuments. Recently,

I did some research on the pavilions that Nicholas

Hawksmoor designed for the gardens of Castle

Howard. The pavilions are predominantly replicas

of ancient funereal monuments; most are placed

on the upper points of the slightly sloping

terrain. In the first monograph on the architect,

the layout of the gardens was described as evoking

a sense of constantly being watched. Similarly,

the steeples of the churches he built in London

are replicas of funereal monuments that are

raised above London’s rooftops, appearing

to watch over and admonish its inhabitants.

In the case of his church in Bloomsbury, the

steeple is a miniature replica of the Halicarnassus

mausoleum – or actually, of a reconstruction

of the mausoleum, which appears to be literally

placed on top. In contrast to this collection

of ancient funereal monuments, it is not at

all clear what the incoherent collection of

statues accumulated over the years in a city

like Rotterdam is to remind us of and how it

relates to the city's contemporary condition.

AA: I’m not sure if it’s safe to

generalise from a case that might be the extreme,

but certainly, examining a system of monuments

like Berlin’s brings to light aspects

of monumentality that are not so obvious in

other cities.

The notion of the super-ego I

mentioned already in connection

with the surveillance comes out of psychoanalysis.

It that context, it is the component of the

personality that extends beyond individual subjectivity

and indeed is often regarded as the internalising

of collective figures of repressive authority.

Aerial Reconnaissance Berlin suggests the Freudian

concept of neurosis could be applicable to a

city. At any rate, I’m prepared to treat

Berlin as a ‘case’.

On the face of it, the symptoms

are abundant.

One could say that monumentality

is the architectural form of

anxiety. As such it is associated

on the one hand with death, and

on the other hand, with neurosis — to

align it with vaguely familiar

Lacanian terms: on the one hand,

the real, and on the other hand,

the imaginary. The monument is architecture

pitched too far, for too much is demanded of

it: to protect us from the dead, to preserve

us till the resurrection, to give meaning to

death. Architecture’s

hyperbole becomes its horizon:

the aspiration that can never be attained, the

ideal that is written into the language of architecture.

To the extent that monuments provide the repertoire

of forms that make up architecture’s self-image,

to be self-consciously a work

of architecture, any building

has to display monumental qualities. That’s

what I mean by the migration of monuments. Partly — there

are also several examples in

Berlin of monuments literally moving from one

place to another, being banished, buried, melted

down, renovated, resurfaced etc.

Architecture, like monumentality,

incorporates the image of its

own ruination, because the image

of the ruin preserves the ideal

that was never attained while

recouping that failure as the pathos of tragedy.

The true hero has to be a broken statue. Ruination

can also make a monument out of a city, as I

discovered in a draft plan for the devastation

of Berlin from the air. [note

1] Most of the ruins of Berlin were

later levelled, but some are

preserved as monuments. Monumentalisation fixes

the desired image for a moment, but at the same

time precipitates the further anxiety that the

ruin will decay, just as much as if it were

an ideal. On the other hand, the decay of monuments

arouses the anxious desire to restore them,

and thus, often, to repress the only thing that

was arousing about them.

An archaeologist will

tell you that the best way to

preserve a find is not to dig

up in the first place, or if

it’s

exposed, to bury it. But that

wouldn’t

satisfy the spectacular demands

of monumentality. In Berlin,

the iconography of the ruin tends

to predominate because the trend, under various

regimes, seems to have been against figurative

monuments: Bismarck was moved from his place

in front of the Reichstag to somewhere in the

woods, the Kaiser Wilhelm Denkmal was demolished,

the statue of Karl Liebknecht was never erected

on the pedestal put up for it,

Lenin was buried in a sand pit on the outskirts

of Berlin. Since 1990, the norm for new monuments

and revisions of old ones has been what I call

sentimental minimalism — a kind of empty

solemnity, that, at its most

bombastic refuses inscriptions.

For instance, the so-called ‘Holocaust’ memorial

(officially, the central memorial

to the ‘Murdered

Jews of Europe’) bears no inscription

except the visitor rules which

state: ‘Alle

Anweisungen des ausgewiesenen

Sicherheitspersonals sind zu

befolgen’ which

should be translated: ‘All

instructions of authorised security

personnel are to be followed.’ Which may

as well replace the whole monument.

The point is, the super-ego function

of monumental sculpture — how

it incorporates repressive authority — can

also be fulfilled by a blind

design-style.

But I wanted to

give just one example of the

fascination and anxiety of ruins.

The Topography of Terror, is an institution

which now occupies the block

near the centre of Berlin formerly

occupied by the headquarters

of various branches of the Nazi security apparatus:

SS, Gestapo etc., buildings previously occupied

by various other institutions — an

art school, a museum of prehistory,

for instance — and

aristocratic mansions. The buildings

were severely damaged during

the war and were later flattened, but the site

was not redeveloped. In the mid-1980s buried

parts of the demolished buildings were excavated

and became the setting for a didactic exhibition

on the Nazi state security institutions and

their victims. The present building and landscape

design is in fact the third attempt to formally

recover the site as a monument. Nothing came

of the first architectural competition. The

prize-winning design of the second was half

built then demolished again. In the present

complex, the exposed remains of the cellars

are displayed for contemplation, while the didactic

exhibition has been moved into a new pavilion

built in an ultra-orthodox minimalist style.

Parts of the foundations of other buildings

have been newly exposed — and

hence are rapidly disintegrating.

Signs indicate where the previous tenants had

set up shop between 1933 and 1945, but nothing

marks the place where the previous, failed attempt

to monumentalise the site was

erased. Whereas in the makeshift Topography

of Terror exhibition of 1987, the quasi-archaeological

remains served to authenticate the didactic

exhibition, now they are preserved as a relict

of the exhibition and serve to authenticate

the institution. Stripped of their annotations,

the remains would be trivial — after

all, this isn’t Rome! — if it weren’t

for their function as ruins in

the monumental landscape design.

The excavations suggest the anxiety of conflicting

desires: to get to the bottom of things — literally,

by exposing the foundations of

Nazi institutions — and

to re-present the recent past

as pre-history — for

which purpose the landscape design

exploits an established repertoire

of architectural readymades — literally,

stuff that’s already there.

TVDP: Is there

something similar going on with

your aerial survey The

State of New York? You

talk about a survey of a map

that’s

turning back into a landscape.

AA:

I’d have to say you are right about

that, although I do something

different with it. There is an

obsessive quality to recording the state of

decay of the terrazzo map in two and half thousand

vertical photographs, and certainly I play with

everything that’s

arousing about ruins and everything

that’s

dizzying about looking down.

The survey I did is also something like what

you expect an archaeologist to

do. The day after I finished

my survey, a team of architectural

conservators started work on the map. They are

actually more used to dealing with ancient

mosaics than terrazzos from the

1960s, but it seems they thought

the New York State Pavilion would

be good practice for their students.

Curiously, the first thing they did was sweep

away everything that my survey recorded, in

order to create their own status

quo ante, which they duly photographed.

Although they claimed to be sensitive

to the ‘philosophical

issues’ of their profession, their idea

of conservation was repairing

the terrazzo panels as if they

really were ancient mosaics,

thus restoring them to the banality that had

inspired their earlier neglect. You can’t

blame a conservator for having a professional

interest in ruins, but the episode

highlights the particular attraction

of this building. The pavilion designed by Philip

Johnson, and advertised at the time as the ‘The

Tent of Tomorrow’ should

have been demolished like the

rest of the World’s

Fair pavilions. It was donated

to the City of New York because

the sponsors wanted to avoid

the demolition costs, but since no permanent

use could be found for the building, it gradually

fell into disrepair, the roof started falling

in and so on, until it really was a ruin. Apparently,

the architect was utterly delighted that his

building had achieved that status. The building’s

accidental prestige and the pathos

of its ruination prompted calls

for its restoration. It’s

probably only in Berlin that

a ruin would proposed as a permanent

use for a derelict building — although,

even there, they probably wouldn’t put

it quite like that.

This is not

the first time that the aspirations

of modernist architecture have

been affirmed by their ruination. Architecture,

as long as it’s architecture, seems bound

to build monuments to a future

that is already lost.

Images

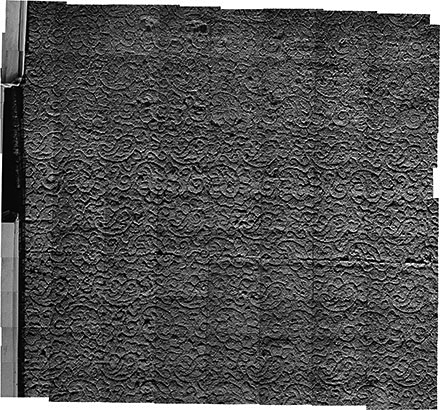

Anthony Auerbach: Planet,

aerial survey, 442 photographs, assembled and

mounted in 4 sections, each 1565 x 1525 mm,

2001 [back

to image]

Berlin:

Schwerbelastungskörper,

1941–42 (photo: Dieter Brügmann,

2005) [back

to image]

Anthony

Auerbach: Troy from Untitled (Cities

and Empires), vertical projection,

aerial survey images, place names,

2008 (installation: Queens Museum

of Art, 2008) [back

to image]

Notes

- Attack on the German Government Machine, draft plan, 15 August 1944 (National Archives), cited in Aerial Reconnaissance Berlin 5.2.(5–6).1[n17]

...

return: urban matters ...

return: urban matters

Statement

to the INS Inspectorate Committee 2009 Statement

to the INS Inspectorate Committee 2009

INS

Inspectorate Berlin: Surveillance Report 2010 INS

Inspectorate Berlin: Surveillance Report 2010

|

|

|

|

|

|