|

|

|

‘The Legendary Origin of Perspective:

notes on Brunelleschi’s manifesto’ by

Anthony Auerbach, paper presented

to the seminar The Penisve

Image,

led by Hanneke Grootenboer, Jan

van Eyck Academie, 2007.

These notes orginally formed part of my MA dissertation, ‘Models of Representation:

A Study in Architecture’s Penumbra’ (MA Advanced Architecture, University of North London [London Metropolitan], 1996). The discussion initated by Hanneke Grootenboer in the seminar The Pensive Image prompted me to revise them. My reflections on the legends of perspective propagated by Panofsky and Damisch follow an extract from Manetti's Life.

From The Life of Brunelleschi by Antonio

di Tuccio Manetti, c. 1480, edited

by Howard Saalman (University

Park and London: Pennsylvania

State University Press, 1970)

He first demonstrated his system of perspective

in a small panel about half a braccio square.

He made a representation of the exterior of

San Giovanni in Florence, encompassing as much

of that temple as can be seen at a glance from

the outside. In order to paint it it seems that

he stationed himself some three braccia inside

the central portal of Santa Maria de Fiore.

He painted it with such care and delicacy in

the black and white colours of the marble that

no miniaturist could have done it better. In

the foreground he painted that part of the piazza

encompassed by the eye, that is to say, from

the side facing the Misericordia up to the arch

and corner of the sheep [market], and from the

side with the column of the miracle of St. Zenobius

up to the corner of the straw [market], and

all that is seen in that area for some distance.

And he placed burnished silver where the sky

had to be represented, that is to say, where

the buildings of the painting were free in the

air, so that the real air and atmosphere were

reflected in it, and thus the clouds seen in

the silver are carried along by the wind as

it blows. Since in such painting it is necessary

that the painter postulate beforehand a single

point from which his painting must be viewed,

taking into account the length and width of

the sides as well as the distance, in order

that no error would be made in looking at it

(since any point outside of that single point

would change the shapes to the eye, he made

a hole in the painted panel at that point in

the temple of San Giovanni which is directly

opposite the eye of anyone stationed inside

the central portal of Santa Maria de Fiore,

for the purpose of painting it. The hole was

as tiny as a lentil bean on the painted side

and it widened conically like a woman’s

straw hat to about the circumference of a ducat,

or a bit more, on the reverse side. He required

that whoever wanted to look at it place his

eye on the reverse side where the hole was large,

and while bringing the hole up to his eye with

one hand, to hold a flat mirror with the other

hand in such a way that the painting would be

reflected in it. The mirror was extended by

the other hand a distance that more or less

approximated in small braccia the distance in

regular braccia from the place he appears to

have been when he painted it up to the church

of San Giovanni. With the aforementioned elements

of the burnished silver, the piazza, the viewpoint,

etc., the spectator felt he saw the actual scene

when he looked at the painting. I have had it

in my hands and seen it many times in my days

and can testify to it.

He made a perspective of the piazza of the

Palazzo dei Signori in Florence together with

all that is in front of it and around it that

is encompassed by the eye when one stands outside

the piazza, or better at, along the front of

the church of San Romolo beyond the Canto di

Calimala Francesca, which opens into that piazza

a few feet toward Orto San Michele. From that

position two entire façades—the

west and the north—of the Palazzo dei

Signori can be seen. It is marvellous to see,

with all the objects the eye absorbs in that

place, what appears. Paolo Uccello and other

painters came along later and wanted to copy

and imitate it. I have seen more that one of

these efforts and none was done as well as his.

One might ask at this point why, since it was

a perspective, he did not make that aperture

for the eye in his painting a he did in the

small panel and the Duomo of San Giovanni? The

reason that he did not was because the panel

for such a large piazza had to be large enough

to set down all those many diverse objects,

thus it could not be held up with one hand while

holding a mirror in the other hand like the

San Giovanni panel: no matter how far it is

extended a man’s arm is not sufficiently

long or sufficiently strong to hold the mirror

opposite the point with its distance. He left

it up to the spectator’s judgement, as

is done in paintings by other artists, even

though at times this is not discerning. And

where in the San Giovanni panel he had placed

burnished silver, here he cut away the panel

in the area above the buildings represented,

and took it to a spot where he could observe

it with the natural atmosphere above the buildings.

Hubert

Damisch asks (himself), ‘What

is thinking in painting, in forms

and through means proper to it?

And what are the implications

of such “thinking” for

the history of thought in general?’ [note

1] Elsewhere he has said, ‘The problem,

for whoever writes about it,

should not be so much to write

about painting as to try to do

something with it, without indeed

claiming to understand it better

than the painter does, [... to

try to] see a little more clearly,

thanks to painting, into the

problems with which [the writer]

is concerned, and which are not

only, nor even primarily, problems

of painting’ [note 2].

These two statements appear to

cross. Are they contradictory?

The first part of the first statement

is a provocative question and

invites us to regard painting

at least hypothetically as a

model of thought and therefore

to ascribe to it, in a profound

sense, originality. The second

part of the same statement is

more ambiguous: it could assign

a relatively easy task to the

historian, namely to describe

how ‘a

painter may very well come to

formulate, by means all his own,

a problematic that may later

be translated into other terms

and into another register (as

happened in its time with perspective)’ [note

3],

but this does not yet say anything

about the ‘implications’ because

such ‘translations’ as Damisch is

hinting at tend to be historical

fictions evoking premonitions,

spirits, mysterious causes and

subjectless intentions. This

procedure, pioneered by Erwin

Panofsky in ‘Perspective

as Symbolic Form’ (1927) [note

4] ascribes

to painting only priority, and

it is hard to see what it can

yield other than metaphors of

dubious historiographic significance.

Thus it would vitiate the idea

of a model of thought. Hubert

Damisch asks (himself), ‘What

is thinking in painting, in forms

and through means proper to it?

And what are the implications

of such “thinking” for

the history of thought in general?’ [note

1] Elsewhere he has said, ‘The problem,

for whoever writes about it,

should not be so much to write

about painting as to try to do

something with it, without indeed

claiming to understand it better

than the painter does, [... to

try to] see a little more clearly,

thanks to painting, into the

problems with which [the writer]

is concerned, and which are not

only, nor even primarily, problems

of painting’ [note 2].

These two statements appear to

cross. Are they contradictory?

The first part of the first statement

is a provocative question and

invites us to regard painting

at least hypothetically as a

model of thought and therefore

to ascribe to it, in a profound

sense, originality. The second

part of the same statement is

more ambiguous: it could assign

a relatively easy task to the

historian, namely to describe

how ‘a

painter may very well come to

formulate, by means all his own,

a problematic that may later

be translated into other terms

and into another register (as

happened in its time with perspective)’ [note

3],

but this does not yet say anything

about the ‘implications’ because

such ‘translations’ as Damisch is

hinting at tend to be historical

fictions evoking premonitions,

spirits, mysterious causes and

subjectless intentions. This

procedure, pioneered by Erwin

Panofsky in ‘Perspective

as Symbolic Form’ (1927) [note

4] ascribes

to painting only priority, and

it is hard to see what it can

yield other than metaphors of

dubious historiographic significance.

Thus it would vitiate the idea

of a model of thought.

Damisch’s second statement suggests that

painting may serve as a model not so much for ‘thought

in general’, but for writing about painting.

And thus, while the field is narrowed, the writer

is issued a serious challenge, and is exposed

directly to the ‘implications’ that

were alluded to in the first statement. A procedure

like this requires a special kind of critical

tact.

Damisch maintains that ‘perspective tends

toward discourse as toward its

own end or reason for being; but it

has its origin [...] on that

plane where painting is inscribed,

where it works and reflects on

itself and where perspective

demonstrates it’ [emphasis

added, note 5]. Damisch’s ‘but’ appears

to mask a reversal of the ambitions

expressed by the two statements

I cited above. Although it appears

in the guise of a ‘finding’ in

the last sentence of his book,

the assertion that ‘perspective tends

toward discourse’ is

really the reiteration of a premise.

Moreover, it seems to narrow

the expectations Damisch holds

out with the concepts of paradigm

or model. Damisch’s ‘tactic’ is

to adopt from the outset an idea

about grammar which is peremptorily

applied to perspective despite

the qualifications and minute

observations that occupy the

author for more than four hundred

pages. The wealth of references

that Damisch offers tends to

make the basic suggestion highly

complex, even fragile, but he

does not actually argue his case.

He asserts, ‘The

formal apparatus put in place

by the perspective paradigm is

equivalent to that of the sentence,

in that it assigns the subject

a place within a previously established

network that gives it meaning

while at the same time opening

up the possibility of something

like a statement in painting:

as Wittgenstein wrote, words

are but points, while propositions

are arrows that have meaning,

which is to say direction’ [note

6].

Damisch would probably accept

that the rationalities of language,

geometry and painting are on

different ‘registers’.

However, I would be hesitant

to suppose that the translations

between them are as easy as he

makes them.

It is as if Damisch wants to say what he thinks

painting shows. He puts himself in the position

of advocate of painting that has chosen to remain

silent (and painting surely has its reasons

for doing so). Far from being so easily subsumed

by discourse, or as Damisch seems to suggest,

destined to be subsumed by discourse, painting

might also be indifferent or hostile to discourse,

even when it deliberately provokes it. Painting

does not speak up, but also it does not — to

employ a Damischian trope — run away (discourir).

If one of painting’s strategies is silence,

it could still be a model of thought, but one

that does not offer an imprimatur. While Damisch’s

tactic succeeds in launching a discourse, perhaps

at painting’s expense, my suggestion would

seem to call it to a halt. Yet it is here that

I would place the potential of a study of perspective

to help elucidate painting’s configuration

of representation historically, precisely in

the way Damisch asks, in forms and through means

proper to it.

The Origin of Perspective hints at

more than one sense for ‘origin’.

Damisch crosses the idea of origin

as source or beginning familiar

from historiography with the

origin we find in geometry (the

intersection of axes) and profits

from the ambiguity he has created.

He is nonetheless detained at

length by the legendary origin,

or invention of perspective.

This is particularly fertile territory for Damisch

because the achievement attributed to Filippo

Brunelleschi of demonstrating rational perspective

for the first time is known only by literary

remains. The two panel paintings Brunelleschi

is said to have made were lost a long time ago.

As a result there is considerable controversy

among scholars about when they were done (dates

have been offered ranging from 1410 to 1425),

what they looked like, and exactly what method

Brunelleschi used to make his famous manifestos.

The most important source, The

Life of Brunelleschi by

Antonio di Tuccio Manetti, believed

to have been written in the 1480’s, is

vague on all these points. The

legend has acquired an almost

mythological import, complete

as it is with hero, secret recipe

and miraculous outcome [note

7]. I do not need to add my own speculation

on the matter. Manetti is precise

enough about some unusual features

of Brunelleschi’s

panels to suggest how these could

reveal some important aspects

of the perspective configuration

that were not so clear afterwards.

This concerns the position of

the subject emphasised by Damisch,

and the meaning of the so-called

vanishing point or, as it is

sometimes called, the eye-point.

I will not give a full account of Damisch’s

interpretation of the Brunelleschi

episode, which contains a detailed,

if unsystematic survey of the

literature, some valuable, if

uncontroversial insights, some

very obscure conjectures and

some blunders [note 8].

I shall try to make what follows as straight-forward

as possible. According to Manetti, Brunelleschi

first made a painting of the Baptistry of San

Giovanni and the surrounding area as seen from

the doorway of the cathedral.

What marks this painting out from the pictorial

tradition until then and afterwards (apart from

the fact that Brunelleschi was not a professional

painter) is the pedantic nature of its method,

which seems to far outweigh the importance of

making a painting of the Baptistry. This is

what makes the designation of it as a manifesto

apt. However trivial the topic might have been

compared with the routine expectations and ambitions

of fifteenth-century painting, it would have

brought the painter to a public place to do

it.

In Manetti’s description, Brunelleschi’s

demonstration is conveyed to us as a mime. Brunelleschi

is said to have drilled a hole in the panel,

through which the viewer was invited to look

from the back, while holding up a mirror in

front of the painting. There are a few highly

suggestive features of this arrangement that

I would like to point out briefly:

- By asking the viewer to approach the

painting from the back, Brunelleschi

declared first of all the opacity

and materiality of the panel.

- The picture itself stood opposite the

Baptistry instead of in front of it.

- The peep-hole offered in the first

place a view of the Baptistry, then in a dramatic

and, one is tempted to say, symbolic gesture

the introduction of the mirror caused the panel

reply with the image of the Baptistry.

- Only then did the viewer find his (or

her) position in the painting.

The theory appears to be the same as the one

familiar from Alberti’s Della

Pittura (1436): ‘a painting

will be an intersection of a

visual pyramid, at a given distance,

with a fixed centre and certain

position of lights, represented

by art with lines and colours

on a given surface’ [note

9].

However, with his painting, Brunelleschi

enacted and embodied what, in

contrast, Alberti articulated

rhetorically (originally his

book was not equipped with the

diagrams that modern editions

provide as a matter of course).

Emphasis in each account seems

to fall on the same spot, although

their respective results are

significantly different. Where

Brunelleschi drilled a hole,

Alberti placed his centric ray or ‘prince

of rays’ [note 10]

By using the mirror to stipulate the viewing

distance (in this case no more than twice arm’s

length), Brunelleschi was able to mark the position

of the eye in the plane of the picture. The

hole, furthermore, enforced the monocular vision

that is consistent with the ‘fixed centre’.

The restriction on the eye and the position

of viewing subject were established unequivocally.

The viewing subject was placed at once in its

position and in the image of its position. By

determining the position of the subject simultaneously

in relation to the picture and in relation to

the Baptistry, Brunelleschi solicited from the

viewer a judgement about the truth of the representation

in so far as it agreed or did not agree with

the reality. (It is worth noting that this painting

would not easily have suggested the ‘convergence’ of

parallels at the eye point, seeing as it is

likely that the scene before the painter did

not contain any conspicuous lines parallel to

line of sight.)

Alberti’s rhetoric on the other hand,

introduced a certain equivocation. He marked

the same spot, but this time as the centric

point, where the prince of rays rules, and towards

which the lines receding parallel to the line

of sight — the ‘orthogonals’ of

his perspective pavement — bend themselves.

This was not quite the ‘point at infinity’ which

mobilised many extravagant commentaries, but

it does take on the appearance of a point quasi

a priori, independent of the subject. Alberti’s

emphasis appears to shift attention from a demonstration

of the possibility of representation, with all

its subjectivity, to the apodixis of geometry,

with its connotations of ideal and objective

truth — not that Alberti goes so far as

to give the mathematical proof he leaves no

doubt he has up his sleeve. The order of things

in which Alberti places both the subject and

the painting is much more obscure than what

is suggested by Brunelleschi’s demonstration.

The equivocation seems to be between displaying

the centric point as the rule that governs the

image, and dissimulating it (in any number of

ways) as the site of the subject. It is possible

to understand the tendency of obscuring the

vanishing point — whether by putting something

in the way in a painting or by hinting in theory

that it lies infinitely far away — as

a tendency toward dissimulating its subjectivity.

Let me look again at Brunelleschi’s demonstration

and try to explain what I mean by ‘demonstration

of the possibility of representation.’

What is it that gives Brunelleschi’s

manifesto the status of an invention?

The geometry and the scientific

optics that Brunelleschi knew

were not at all primitive, but

there was nothing in them to

suggest a way of making naturalistic

pictures. The innovative concept

was the intersection, as Alberti

called it. The innovative technique, the invention,

was what we call the picture plane. Painting

on a flat surface was nothing new, but previously

it did not define painting, nor

were flat painting surfaces necessarily the

norm. The picture plane that Brunelleschi demonstrated

in his complication of perspective is a new

kind of object. It is an object with a special

and possibly unprecedented ambiguity. (One might

add: a fateful one, because henceforth

irrevocable.) The ambiguity arises out of the

fact that what is at stake is appearance. In

short, we perceive as objects both the thing

depicted ‘in

the picture’ and the

picture itself. The picture plane

is the substance which bears

the lines and colours proper

to painting. However, the intersection,

in its concept, denies that substance,

in so far as the space ‘beyond’ the

picture plane is supposed to

be continuous with that before

it. The paradox for the painter

is that to depict something,

the picture as an object must

have the utmost integrity if

it is to succeed in disappearing. Alberti’s

declaration that the painting

is ‘an open

window through which the subject

to be painted is seen’ [note

11]

masks an avoidance of this paradox.

The geometry of the picture plane — the

amazing convergence of parallel

lines — is

only surprising if it is interpreted

as a Euclidean plane, instead

of as a plane of projection.

The desire for truth-to-appearance which is

demonstrated and tested in Brunelleschi’s

manifesto (whether is was sought

for its own sake or for the sake

of the historia,

as Alberti has it) precipitates

in painting a new form of representation.

Although painting always operated

as much by resemblance as by

any other means and is not entirely

reducible to picture-writing,

the predominant mode of signification

of painting before Brunelleschi

made his mark was (crudely speaking) ‘symbolic’ in

the following way: the sign stands

in a relation of identity to

what it signifies. It stands for the

latter, is arbitrary, objective

and relative. When painting assumes

the mode of signification that

Peirce would call ‘indexical’ (though

it hardly relinquishes its symbolic

moments). It stands in a mediated

relation to what it signifies.

It stands against the

latter, is contingent, subjective

and absolute [note 12].

In the first case, painting things is like

naming them. The meaning of the

painting thus depends on borrowed

systems, arguably, is not proper

to painting. In the case of Brunelleschi,

the painting represents a complete

situation, that is, complete

with subject, object and what’s

in between [note 13]. Hence

it is closer to being a proposition

in its own right in the way Wittgenstein

uses this term — ‘Situations

can be described but not given

names. (Names are like points;

propositions like arrows — they

have sense.)’ [note 14] — which

is perhaps why Damisch felt that

perspective tended towards discourse,

but I think he misreads Wittgenstein’s

clues. Wittgenstein’s theory (in the Tractatus)

is instructive because what it

aims to elucidate is the structure

of language, that is, the structure

of representation. It is not

far-fetched to suggest that this

is also the point of Brunelleschi’s

demonstration. The discipline

that would characterise a demonstration

could explain the eccentric manner

in which Brunelleschi executed

his panels. This demonstration

has the right to be called a ‘proposition’ if

we accept, with Wittgenstein,

that ‘A proposition

is a model of reality as we imagine

it’ [note 15].

Wittgenstein’s theory is not needed however

to show that the power of representation

that Brunelleschi demonstrated

does not stem from his use of

geometry (if he used it) but

from the fact that the perspective

configuration has the structure

of a model. The perspective configuration

keeps this structure even when

it fades into the background [note

16] or is

asserted only in symbolic form.

...

return: On theory ...

return: On theory

...

return: Jan van Eyck Academie ...

return: Jan van Eyck Academie

Notes

- Hubert Damisch, The Origin of Perespective

(Cambridge MA and London: MIT

Press, 1994), p. 446. [back

to text]

- Hubert Damisch, Fenêtre jaune

cadmium, ou les dessous de la peinture, p. 288. ‘le

problème, pour qui en écrit, ne

devrait pas tant être d’écrire

sur la peinture, que de tâcher à faire

avec elle, sans prétendre en effet la

comprendre mieux que ne le fait le peintre,

mais dans l’idée plutôt [...]

d’y voir un peu plus clair, grâce à la

peinture, dans les problèmes qui l’occupent

lui-même, et qui ne son pas seulement,

ni même d’abord, des problèmes

de peinture.’ [back to

text]

- Fenêtre jaune cadmium,

p. 288. ‘sans recourir à la théorie,

ni à la mathématique, un peintre

peut fort bien en venir formuler par les moyens

qui sont les siens ne problématique qui

pourra ensuite être traduite en d’autres

termes et dans un autre registre (ainsi en aura été,

en son temps, de la perspective).’ [back to

text]

- Erwin

Panofsky, Perspective as Symbolic Form, trans.

by Christopher S. Wood (New York: Zone Books,

1991). Activating what is effectively a pun

between perspective and Weltanschauung, or world-view,

Panofsky adopts perspective itself, that is,

projection, as the ‘heuristic model’ for

interpreting it, and employs the short-circuit

as a short-cut. The results are: 1. that the

correspondences he describes are assumed to

be necessary and transparent before he has asked

whether this is so in the history of perspective

itself; and 2. that his hypotheses about history

are shielded from enquiry. The historical material

he presents with the meticulous scholarship

for which he is renowned is allowed to slide

suddenly into a ‘perspective scheme’,

a ‘world-view’, a ‘conception

of space’. In the introduction to his

1991 English translation Christopher S. Wood

says, ‘The practice or tactic of the essay

is to juxtapose an art-historical narrative

and a characterisation of Weltanschauung (which

is often achieved by a narrative about intellectual

history), and then marry them in a brief and

dramatic ceremony.’ [back to

text]

- The Origin of Perespective,

p. 447. [back to

text]

- The Origin of Perespective, p. 446.

The paraphrase of Wittgenstein provides a pun

on ‘points’ which are one of Damisch’s

preoccupations, and presumably a special kind

of emphasis in the original French, where the

same word, sens, gives ‘meaning’, ‘sense’ and ‘direction’. [back to

text]

- Antonio di Tuccio Manetti, The Life of Brunelleschi,

ed. by Howard Saalman (University Park and London:

Pennsylvania State University Press, 1970).

The entry in the catalogue of the National Art

Library in London classes Manetti’s book

as fiction. [back to

text]

- For example, Damisch appears to

imagine a ‘subject’ with eyes protruding

from its skull. [back to

text]

- Leon Battista Alberti, On

Painting, trans. by Cecil Grayson (London: Phaidon

Press, 1972), p. 48. [back to

text]

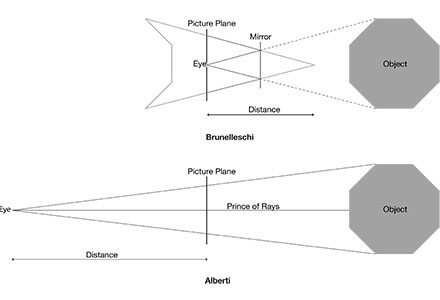

- The diagrams I have

drawn above are intended to demonstrate the

difference between Brunelleschi’s and

Alberti’s configurations. [back to

text]

- On Painting,

p. 54. [back to

text]

- Here, I accept the broad distinctions

inherited from Peirce’s more complex theory

and Hermann Weyl’s précis: ‘...the

objective state of affairs contains all that

is necessary to account for the subjective experiences.

... It comprises as a matter of course the body

of the ego as a physical object. The immediate

experience is subjective and absolute. However

hazy it may be, it is given in its haziness

and not otherwise. The objective world, on the

other hand, ... is of necessity relative; it

can be represented by definite things (numbers

or other symbols) only after a system of co-ordinates

has been arbitrarily carried into the world.

It seems to me that this pair of opposites,

subjective-absolute and objective-relative,

contains one of the most fundamental epistemological

insights which can be gleaned form science.

Whoever desires the absolute must take the subjectivity

and egocentricity into the bargain; whoever

feels drawn toward the objective faces the problem

of relativity.’ [Philosophy of Mathematics

and Natural Science, trans. by Olaf Helmer (Princeton:

Princeton University Press, 1949), p. 116–117.] [back to

text]

- This is also true of Alberti’s concept

of the intersection and his veil, but not of

the method of construction he recommends to

painters. [back to

text]

- Ludwig Wittgenstein, Tractatus

Logico-Philosophicus, trans. by C. K. Ogden

(London and New York: Routledge & Kegan

Paul, 1961), §3.144. [back to

text]

- Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, §4.01.

One has to watch the ‘... as we imagine

it.’ Moreover, when the philosophers get

their metaphors from art history, one should

be careful not to imagine they explain it. [back to

text]

- As is the case with ‘normal’ paintings

following Alberti, which may make claims to

the naturalistic depiction of appearance, but

do not enforce the viewing point like Brunelleschi’s

first peep-show demonstration. It is worth underlining

that Brunelleschi’s second panel, although

it dispensed with the peep-hole, it was not

an Albertian window either, because it was not

rectangular. By cutting out the buildings and

letting their profiles stand out against the

sky, Brunelleschi appears to be making a point

of the limits of the operation of perspective

(as he had suggested by the mirrored sky on

the first panel), a scruple that was not followed

in such an obvious way by the painters that

took up the method after him. [back to

text]

|

|

|

|

|

|