|

|

|

‘Joining the Dots: The Historical

Appearance of “Geometric” Constellation

Figures’, research project by Anthony Auerbach.

A true Astronomer feigns

nothing without solid and sufficient Reasons, he

takes Nature for his Guide and Rule, and lays his

Foundations on Observations: He raises his System

on Physical Causes, and invincible Geometrical Demonstrations,

with which, as with an indissolvable Cement, he joins

and Binds the whole Fabrick together. [note 1]

Linking

the brightest stars with straight

lines on a map to form quasi-geometric

figures is probably the form

of the constellations most familiar

to contemporary visual culture.

Although it is widely assumed

to be the essential, the original,

even the ‘natural’ way

of drawing the constellations,

this form was not widely adopted

before the nineteenth century.

It became the norm in the twentieth

century, where constellation

figures survived, but was never

officially sanctioned [note

2]. Linking

the brightest stars with straight

lines on a map to form quasi-geometric

figures is probably the form

of the constellations most familiar

to contemporary visual culture.

Although it is widely assumed

to be the essential, the original,

even the ‘natural’ way

of drawing the constellations,

this form was not widely adopted

before the nineteenth century.

It became the norm in the twentieth

century, where constellation

figures survived, but was never

officially sanctioned [note

2].

The earliest printed map to

propose a system of ‘geometric’ constellation

figures to replace the traditional

figurative star signs appears

to be the Nouvelle

Uranographie (1786) by Alexandre

Ruelle [note 3].

Unlike other attempts at the

reform of the constellations

such as Schiller’s

Coelum Stellatum Christianum (1627)

[note 4], the Nouvelle

Uranographie was a success. As a

result, this map lost its place

in history. Whereas the various

failed attempts at reform are

still admired as historical curiosities — that

is to say, as objects without consequences — the Nouvelle

Uranographie falls into history's blind

spot.

The history of celestial cartography

is usually thought to have come to an end

at the turn of the nineteenth

century. Johann Bode’s

Uranographia (1801) is widely regarded

as the last and most magnificent

star atlas in the tradition which

reaches back to Ptolemy. Bode’s

atlas is a museum of astrography

[note 5]. It not only aggregated

the sum of observational data

and cartographic customs, but

augmented the latter with several

new constellation figures. After

Bode, the antiquarians note with

regret, star maps display either

the triumph of professional science

over the art of cartography,

or the vulgarisation of amateur

astronomy, served increasingly

with cheap, industrially produced

maps, books, gadgets and toys.

On this view, the Nouvelle Uranographie

would appear as a premature announcement

of the end of celestial cartography’s ‘golden

age’ and would thus tend to deprive the

standard history of its culmination.

Acknowledging the novelty

of the Nouvelle

Uranographie, however,

would tend to deprive subsequent

maps of the primordial authority

of ‘geometric’ figures

invoked by the promoters of

such maps (if not by historians) — those

figures which according to Galileo’s assertion

[note 6] are the characters

in which the book of the universe

is written and in which philosophy

shall be read.

Nonetheless, Ruelle’s

map is marked by the history

in which it was eventually engulfed. Having

first appeared in 1786 bearing a royal dedication,

the map’s alterations and resurfacings

(authorised or plagiarised) record

the upheavals which

revolutionised not only

the affairs of state, but also

the regime of what was soon to

become the Observatoire de la

République. By 1795, Ruelle himself

appears to have abandoned the

institution that had once been

his refuge,

‘la révolution l’ayant enlevé à l’astronomie’

[note 7].

Research will disclose the historical juncture

in which the Nouvelle Uranographie emerged — at

the convergence of astronomy

and cartography which dominated

the activities of the Paris Observatory

in the eighteenth century; at

the divergence of amateur and

professional astronomy which

came to dominate map production in the nineteenth

century; at the submergence of speculative histories

of astronomy that were discredited even as the

map’s innovation

was accepted — as well as how the writing

of history swept the map and

its author into obscurity.

Interpretation faces an anomalous object. Like

the figures which lend form to

discrete astronomical data, interpreting

the Nouvelle Uranographie will have

to deal with loose ends and disconnected

facts: with historical dead-ends.

It will risk being led by Ruelle

— whose name in French means

back alley — away from the main

street of history.

...

return: On cartography ...

return: On cartography

Notes

- John Keill, An Introduction

to the True Astronomy: Or,

Astronomical Lectures,

London: Bernard Lintot, 1730,

p. 27. Italics in the original. [back to text]

- The International Astronomical

Union had, at its founding in

1919, nominated the eighty-eight

constellations that would be

officially recognised and rigourously

defined by their boundaries.

The task of the scientific definition

of the constellations was entrusted

to Eugène Delporte and

published in the Délimitation

scientifique des constellations (Cambridge

University Press, 1930). The

boundaries defined on Delporte’s

map according to the geometric

division of the sphere into parallels

and meridians are the vestigial

outlines of a tradition it was

Delporte’s task both to

liquidate and to uphold. [back to text]

- Alexandre Ruelle, Nouvelle

Uranographie ou Méthode très

facile pour apprendre à connoitre

les Constellations, (Paris: Dezauche, de

la Marche et Jombert, 1786). [back to text]

- Julius Schiller, Coelum

Stellatum Christianum

(Augsburg: Andreae Apergeri, 1627). [back to text]

- Johann Elert Bode, Uranographia (Berlin: Frederico

de Haan, 1801). The atlas featured Ptolemaic

and non-Ptolemaic constellations as well as

ecliptic and equatorial graticules. The western tradition of printed maps stems

from the Renaissance. [back to text]

- Galileo Galilei, The Assayer (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1957), pp. 237–238. [back to text]

- Jérôme de Lalande, Bibliographie astronomique avec l'histoire de l'astronomie depuis 1781 jusqu'à 1802 (Paris: Impimerie de la République, 1803), p. 596. [back to text]

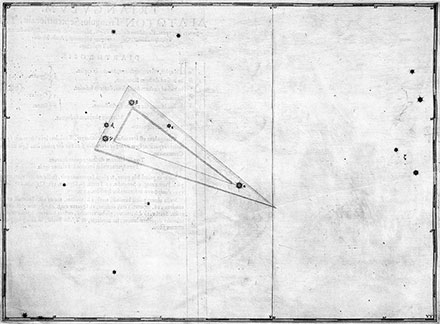

Images

Triangulum from Johann Bayer, Uranometria (Augsburg, 1603)

|

|

|

|

|

|