|

|

|

‘I Rode a Gelatin Motorcycle’ by

Anthony Auerbach, in

La Journal [sic], Paris: ARC/Musée

d’Art

Moderne de la Ville de Paris,

29 February 2008, p. 25.

“I Rode a Gelatin Motorcycle” is

probably the ideal title for a dubious memoir

and apt enough, since I’m unlikely to

have another opportunity to use a headline of

this genre. “I Was a Teenage Gelatin” has

got potential, but, like “I Was a Male

Gelatin Bride”, it isn’t a piece

I could write. “I Was a Communist for

Gelatin” is stretching it, but I could

probably put my name to “I Was a Mouthpiece

for the Gelatin Military” or “I

Paid Gelatin”. “I Rode a Gelatin Motorcycle” is

probably the ideal title for a dubious memoir

and apt enough, since I’m unlikely to

have another opportunity to use a headline of

this genre. “I Was a Teenage Gelatin” has

got potential, but, like “I Was a Male

Gelatin Bride”, it isn’t a piece

I could write. “I Was a Communist for

Gelatin” is stretching it, but I could

probably put my name to “I Was a Mouthpiece

for the Gelatin Military” or “I

Paid Gelatin”.

First the background. In 1999 there was a general

election in Austria. Some months later (in 2000),

after a lot of horse trading a new government

was announced, a coalition between the ÖVP

(People’s Party) and the FPÖ (Freedom

Party). This was a novelty in so far as ever

since the republic was formed in the aftermath

of the Second World War, national affairs had

been dominated by the left-wing Socialist Party

and the right-wing People’s Party, or

a cosy arrangement between the two. The participation

in government (based on 27% of the popular vote)

of the misnamed Freedom party, led by the notorious “designer

Fascist” Jörg Haider got Austria

a lot of bad press abroad and upset many lazy

left-wingers at home, especially artists who

generally relied on the government for their

livelihood. The state is the main financial

supporter of so-called culture in Austria and

had in recent years invested heavily in contemporary

art. The aim of the policy is, in part, to deflect

attention from the fact that the conditions

that had made lively, modern(ist), avant-garde,

even critical cultural production — such

as is associated with Vienna circa 1900 and

the names Freud, Kraus, Schoenberg, Loos, Wittgenstein,

Kokoschka, Klimt, Schiele etc. — what

had made it possible in (spite of) a basically

conservative and anti-Semitic society had been

completely and irrevocably destroyed by the

Austrians during the Nazi period. Among the

results of the recent policy of lavish support

for artists and institutions were 1. a mildly

sado-masochistic relationship between the artistic

and political elites (who in any case belong

to the same class), and 2. a tendency among

artists to consider themselves public — even

political — actors, while nonetheless

claiming their privileges as rights supported

by the supposedly universal mission of art (for

example, as declared on the façade of

the ridiculous Secession building in Vienna).

Consequently, when the new government was announced

in 2000, including a party which was disliked

but largely unopposed by Austrian liberals,

and generally regarded as extreme in other parts

of Europe, the self-styled artistic community

was outspoken it its opposition. Opposition,

that is, to the result of an election which

they had done nothing to influence before the

vote, for instance, by campaigning for the Socialists

or attacking the populist (racist) right-wing

campaign. Declarations were made. Websites were

set up. Protests were called. A prominent curator

called for a cultural boycott and proudly announced

his self-imposed exile from Austria (conveniently,

he already had a job abroad). The same curator

did not explain publicly why he changed his

mind when he recently accepted, from to all

intents and purposes the same government he

had earlier denounced, the position of state

commissioner of the Austrian Pavilion at the

Venice Biennial. Less eminent characters in

the Austrian art world reacted to the new government

like disgruntled civil servants concerned about

a change in the superior levels of the administration

(although, in fact, their immediate superiors

did not change).

Around this time, I was sharing an apartment

in New York with Wolfgang and Florian. Happily,

I had some time off since I had just suspended

the visual arts programme I had been organising

for the Austrian Cultural Institute (ACI) in

London. The programme had been launched in the

Summer of 1999 (including Gelatin’s London

debut — “Breakfast in Bed with Gelatin” followed

by “The Gelatin Ship Paprika”, which

would be another hair-raising story but would

explain how we became friends). The programme

for the ACI was meant to be independent and

international, but this was impossible to demonstrate

in the atmosphere produced by the media storm

about new Austrian government. I had no intention

of helping the Austrians out of their own diplomatic

pickle or letting it compromise my work. The

sudden loss of credibility of the host and sponsor

of the programme was bad enough, but the solemn

statements by Austrian artists were really embarrassing.

In New York, we heard that a group of expatriate

Austrian artists (some on state-sponsored scholarships)

had decided to stage a protest and had called

a meeting to which Wolfgang and Florian were

duly invited. I should explain, I was not invited

because I’m not Austrian. A discussion

erupted at our kitchen table because Wolfgang

thought they should go and check it out and

Florian was convinced (from prior knowledge

of the people in question) that it wasn’t

worth it. I was neutral, but had some fun discussing

what the meeting could be about and what kind

of protest would make sense anyway. It seemed

to me one ought to find a form of action which

was stupid enough for artists to do, but directed

at the right people to drive the message home

as quickly as possible. The gay “We love

Haider” parade, the Vaseline on the door-knobs,

the Superglue in the keyholes, the swastikas

in the elevators of the ACI and the like would

have the Austrian diplomats in New York complaining

to their superiors that they just can’t

stand it anymore.

The result of the discussion was that Florian

was persuaded, reluctantly, to go to the meeting.

So I said, “Bye, have a nice time.” To

which Florian replied, “No. You’re

coming with us.” On the way there, in

an attempt to calm Florian’s irritation

at being forced to reserve his judgement, I

suggested, “We’ll know they are

really full of shit if they are having a vote

at this meeting.” When we finally arrived

at the meeting, which had actually started some

hours earlier than we thought, everybody had

their hands in air voting on the draft press

release about their protest and the slogans

they should use on their placards. Apparently,

someone had taken the initiative of asking the

director of the Austrian Consulate in New York

whether it was OK to hold a protest outside

the building. He said it would be fine since

nobody would be there on a Saturday.

The press release about to be endorsed by a

consensus amounted to an exercise in ingratiating

oneself with authority. Its content was pretty

much the same as the declaration which the Austrian

President had forced the party leaders Schüssel

and Haider to sign when they got into bed together.

Added by the artist-group to those banalities

about human rights was special pleading for

artists. It did not contain any news which could

possibly be of interest to the press in New

York. I won’t even mention the slogans.

In the group discussion which continued a little

bit, some of the suggestions from our kitchen

table emerged into the room in Wolfgang’s

most reasonable voice or accompanied by daddy-longlegs

gesticulation from Florian’s corner of

the room. This caused a little consternation,

but the discussion soon ended because everything

was already decided by a vote.

Someone must have noticed the astonished expression

on my face and I was asked what I thought about

the plan just decided. At first, I declined

to answer, because this was really none of my

business. However, I was pressed and I relented.

I explained that if you are going do a press

release, it has to contain news about an event

worth reporting, or one that local people might

want to go to. It has to be addressed accurately

to the journalists you want to cover the event

and through them to their readers. I must have

spoken with some confidence, although this was

still quite early in my career as a propagandist.

The Summer’s events in London had more

or less proved that a well-crafted press release

and a well-organised campaign could get large

numbers of people to do unlikely things, get

yet more people to talk enthusiastically, and

even get some to lie about their experience.

More than a thousand people came to take a ride

on a spaceship made by Gelatin out of clingfilm

and waste cardboard, in a filthy, derelict,

subterranean former railway goods yard off Brick

Lane.

Many of the earlier-assembled Austrian artists

had by this time regrouped to hear this explanation

(others had gone off to make absurd placards).

Wolfgang and Florian also elaborated somewhat

on the kitchen-table suggestions. While the

earlier phase of the meeting had been appalling,

now it was alarming how quickly the group was

won over by the suggestions we put forward. “Anthony,

won’t you give us just a few lines for

our press release,” they pleaded. I did

not comply. A handful of people showed up with

placards on the Saturday and they stuck with

the original press release. E-mails started

to circulate about subversive tendencies instigated

by “Gelatin and Anthony”.

In 2001, when Gelatin appeared to represent

Austria at the 49th Venice Biennial, I was called

in by Gelatin to be their official press spokesman.

By the time I arrived in Venice the Gelatins

were not on speaking terms with the commissioner

any more (not the same commissioner I mentioned

above, this one was both less scrupulous and

less hypocritical). So I had the pleasure of

explaining to the Austrian and international

press what looked like a complete disaster.

Simple: take a small amount of a substance called

Gelatin, just add water. I was asked if the

swamp we were standing in (already colonised

by plants, snails, frogs, fish and sloths) was

some kind of political allegory. I don’t

remember what I said in reply.

Note

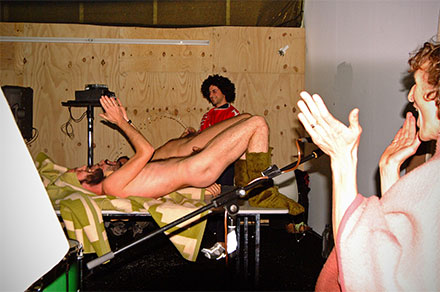

Gelatin is the substance, Gelitin is a brand. Images

Gelatin and Anthony: Frieze Art Fair, 2003, photograph: Vargas Organisation, London

|

|

|

|

|

|